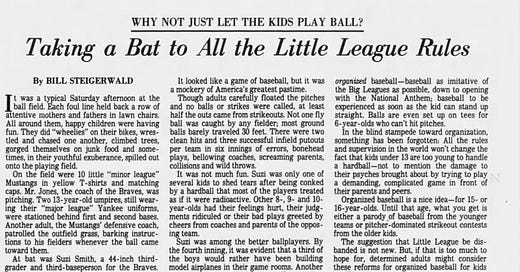

While we're at it, let's cancel Little League

What I witnessed looked like a game of baseball, but it was a mockery of America's greatest pastime.

I’m a lifelong lover of baseball and lifelong hater of organized youth sports for kids under 14. I wrote this opinion piece for the Los Angeles Times in 1980 after witnessing an archetypal little league baseball game in San Francisco. It was syndicated around the USA and I got a lot of spirited letters, pro and con. Everything I said about what was wrong with youth baseball then — too organized, too many meddling adults — is still true today. Other baseball-centric features from the 1980s include one about the time I spent with Tommy Lasorda and a location piece on the John Sayles movie “Eight Men Out.”

It was a typical Saturday afternoon at the ball field.

Each foul line held back a row of attentive mothers and fathers in lawn chairs.

All around them, happy children were having fun. They did "wheelies" on their bikes, wrestled and chased one another, climbed trees, gorged themselves on junk food and sometimes, in their youthful exuberance, spilled out onto the playing field.

On the field were 10 little "minor league" Mustangs in yellow T-shirts and matching caps. Mr. Jones, the coach of the Braves, was pitching.

Two 13-year-old umpires, still wearing their "major league" Yankee uniforms, were stationed behind first and second bases. Another adult, the Mustangs defensive coach, patrolled the outfield grass, barking instructions to his fielders whenever the ball came toward them.

At bat was Suzi Smith, a 44-inch third grader and third-baseperson for the Braves. She waited patiently for the pitch, her silvery aluminum bat cocked perfectly.

Mr. Jones lobbed the slowest overhand pitch that the laws of God and Newton would allow. The official Little League baseball struck Suzi on the shoulder, and she crumpled in the dust of the batter's box.

Coaches and parents rushed to home plate. As they escorted Suzi to the bench, she cried as if her arm as well as her pride were broken. But she recovered quickly and, following the scattered applause of several adults, quickly grounded out to first.

The game progressed.

The Mustangs and the Braves swung regulation Little League bats at regulation Little League balls. They were protected by batting helmets and catcher's gear. They raced down freshly limed and measured basepaths in size 3 spikes.

They carried Flexomatic-palm mitts ($80 Tom Seaver autograph model), and wore numbered uniforms and used detailed score books and had impartial umpires.

Everything was organized and properly supervised, and everybody got to play at least three innings on take at least one turn at bat.

It looked like a game of baseball, but it was a mockery of America's greatest pastime.

Though adults carefully floated the pitches and no balls or strikes were called, at least half the outs came from strikeouts.

Not one fly ball was caught by any fielder. Most ground balls barely traveled 30 feet.

There were two clean hits and three successful infield putouts per team in six innings of errors, bonehead plays, bellowing coaches, screaming parents, collisions and wild throws.

It was not much fun for the kids.

Suzi was only one of several players to shed tears after being conked by a hardball that most of the kids treated as if it were radioactive.

Other 8-, 9- and 10- year-olds had their feelings hurt, their judgments ridiculed or their bad plays greeted by cheers from from coaches and parents of the opposing team.

Suzi was among the better ball players — girls and boys.

By the fourth inning, it was evident that a third of the boys would rather have been building model airplanes in their game rooms. Another third would have been better off practicing piano or doing homework.

Only 6 of the 30 Mustangs and Braves seemed to have the basic physical and mental skills needed to play baseball. Their coaches weren't in much better shape.

The game, typical of thousands played across America every Saturday of spring and early summer, was full of examples of why organized baseball for youth has attracted so much criticism since its inception in Williamsport, Pa., in 1939.

Little League, in all its variations, is now as sacred to America as manicured lawns, women's clubs and matched socks.

It's everywhere, but it's not monolithic. Every township has its special rules and bylaws. There are player drafts and no-parent rules, and rules about contracts and eligibility, and mandatory two-day-rest rules for starting pitchers.

But the rules merely institutionalize what's wrong: organization.

For some reason, adult America has deemed it important, almost obligatory, that its youth — now girls as well as boys — experience the joys of organized baseball.

Not just baseball, organized baseball — baseball as imitative of the Big Leagues as possible, down to opening with the National Anthem. Baseball to be experienced as soon as the kid can stand up straight. Balls are even set up on tees for 6-year-olds who can't hit pitches.

In the blind stampede toward organization, something has been forgotten:

All the rules and supervision in the world won't change the fact that kids under 13 are too young to handle a hardball — not to mention the damage to their psyches brought about by trying to play a demanding, complicated game in front of their parents and peers.

Organized youth baseball is a nice idea — for 15- or 16-year-olds.

Until that age, what you get is either a parody of baseball from the younger teams or pitcher-dominated strikeout contests from the older kids.

The suggestion that Little League be disbanded is not new. But, if that is too much to hope for, determined adults might consider these reforms for organized baseball for kids under 15:

— Use a softball — a very soft softball — and pitch underhand. The kids will hit the ball more often and be less ball-shy, pitching arms won't be prematurely ruined and games will no longer be dominated by big kids who strike out everyone.

— Hold tryouts. If a boy or girl can't pass a fundamental test of hitting and fielding skills, tell him or her to come back next year. Playing organized baseball is neither a constitutional right nor an end in itself.

— Ban parents. Play on weekday summer mornings with college kids supervising. Keep the schedule secret, prohibit parents from coaching or umpiring and forget about uniforms and National Anthems.

The best conceivable youth baseball program, if there must be one, would be to employ a sincere, dedicated adult to drop off a set of bases, a couple of balls and a bat or two at each local field in the morning — and then disappear until it's time to collect them at dusk.

Ah, this is so so true!