World Series, 1919 -- On location with 'Eight Men Out'

Many seasons ago John Sayles and his young stars went on the road to make his realistic baseball movie about the time the 'Chicago Black Sox' threw the World Series. I caught up with them.

In the fall of 1987 I flew from LA to Indianapolis and spent four days on the location set of the baseball movie “Eight Men Out.”

I got to play catch and shag fly balls with jocky young movie stars like John Cusack and Charlie Sheen and watch brainy John Sayles direct a movie about one of baseball’s historic scandals.

Along with this location piece are links to some of my baseball-centric hits and foul balls from the 1980s that have been only slightly scuffed by time: A XXX-rated Tommy Lasorda feature, an anti-Little League rant, that was syndicated around the country, my Vin Scully interview and a 2002 interview with political pundit George Will about his favorite game.

The Fall Guys

Bush Stadium, Indianapolis, 1987

Cool and sunny and October -- a perfect day to make a baseball movie.

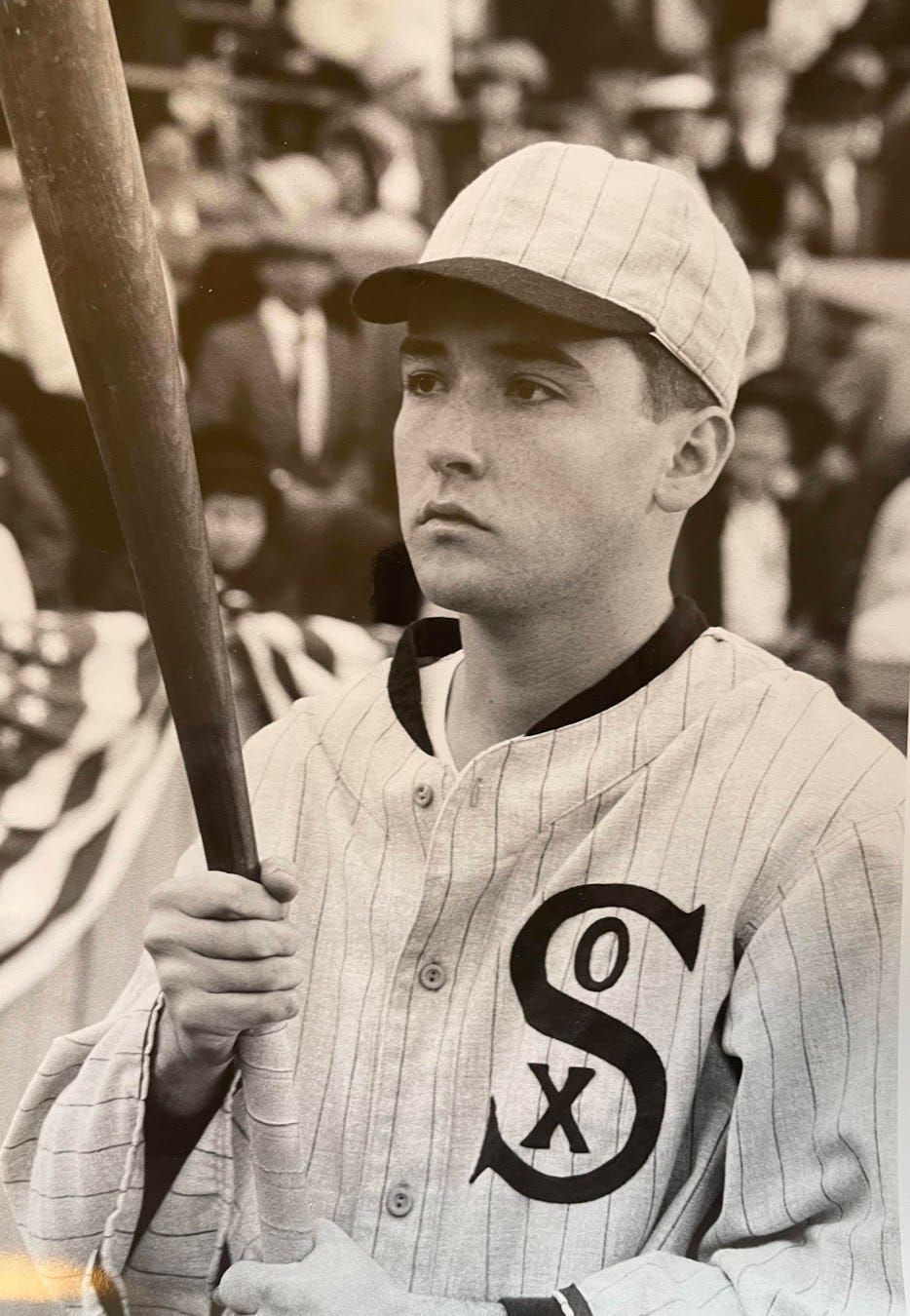

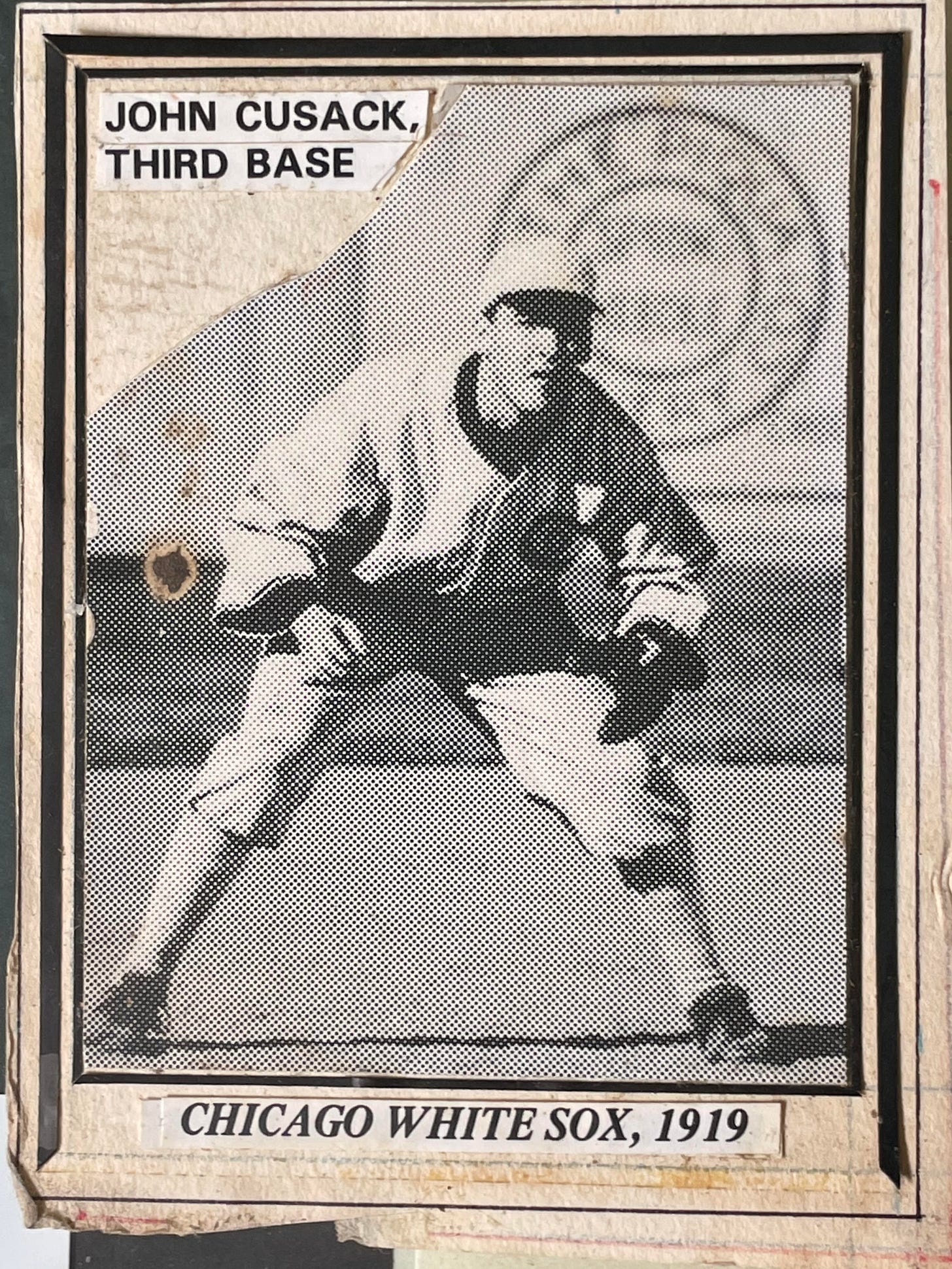

At third base is John Cusack.

Dressed in a baggy gray-and-black-striped Chicago White Sox uniform from 1919 and wearing a primitive glove of the era, he scrapes up clouds of Bush Stadium’s thick red infield dirt with his metal cleats. Then he coils into a crouch, weight forward, hands down, head up, eyes fixed toward home plate. He’s ready.

Director John Sayles yells over to Ken Berry, a former major leaguer standing off-camera on the third base line in front of Cusack with a baseball and a wood bat: “Don’t be afraid to get a hit, Ken!”

“You can’t hit it by me!” taunts Cusack, 21, punching his fist into a pathetic rag of a mitt that’s three times older than he is.

It is a bold but empty boast and Cusack knows it.

His stumpy, web-less glove provides scant help in fielding anything hit hard. To catch a ball cleanly, he must snare it squarely in his palm--and then suffer the sting that rips through the thin leather.

But Cusack is game. After all, he’s living out Everyboy’s Dream. He’s playing in the World Series--the scandalous White Sox-Reds World Series of 1919 that became known as the “Black Sox Series” after it was learned that eight Sox players had conspired with East Coast gamblers to deliberately lose to the greatly overmatched Reds.

Bush Stadium, the spacious home of the Montreal Expos’ top farm club, the Indianapolis Indians, has been done over by Hollywood cosmeticians to resemble Cincinnati’s long-gone Redland Park.

It’s been decked out in red-white-and-blue bunting and given weathered wooden dugouts. Its red brick walls are hidden behind a weathered 40-foot wood facade that’s been painted with period billboards advertising things like Youngs Hats and Louisville Slugger bats and Whittemore’s shoe polishes.

Cusack’s character is Buck Weaver, the scrappy star third baseman of the powerhouse White Sox. He and seven teammates--including left fielder Shoeless Joe Jackson (of “Say it ain’t so, Joe” fame), whom historians assert was one of the greatest natural hitters ever--were ultimately banned from baseball for life for their part in America’s greatest known sports swindle. (Though they were acquitted of all charges by a grand jury, they were nevertheless banished by baseball commissioner Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis: “No player that undertakes or promises to throw a ball game . . . will ever play professional baseball!”)

The definitive account of the origins and aftermath of baseball’s worst hour was told in Eliot Asinof’s best-selling 1963 book, “Eight Men Out.” Asinof explained how disgruntled first basemen Chick Gandil approached gamblers with the idea of throwing the Series and then recruited seven teammates to make a host of subtle but damaging mistakes on the field.

Asinof also detailed the not-so-innocent world of baseball that existed then. It was a sport run by wealthy team owners who treated their underpaid players like chattel, a sport where the outcome of games was regularly rigged by players in cahoots with gamblers.

Sayles faithfully followed the book when writing the script for the movie “Eight Men Out,” which is due out from Orion Pictures next summer. A complex ensemble piece budgeted at $6-million-plus, it has 17 major and 35 supporting roles.

It’s deep with seasoned New York actors (Bill Irwin, David Strathairn) and young Hollywood upstarts--Cusack (“Sure Thing”), Charlie Sheen (“Platoon”) and D. B. Sweeney (“Gardens of Stone”). Sayles himself plays newspaperman Ring Lardner. Author-radio host Studs Terkel plays a sportswriter.

In Search of Authenticity

“Heads up!,” warns Sayles. He calls for action and Berry, a Gold Glove outfielder with the White Sox and Angels in the mid-'60s and early ‘70s, nubs a soft liner that’s grabbed easily by Cusack.

“Really whack ‘em, Ken,” urges Sayles, whose big-boned frame miniaturizes the director’s chair he’s sitting in.

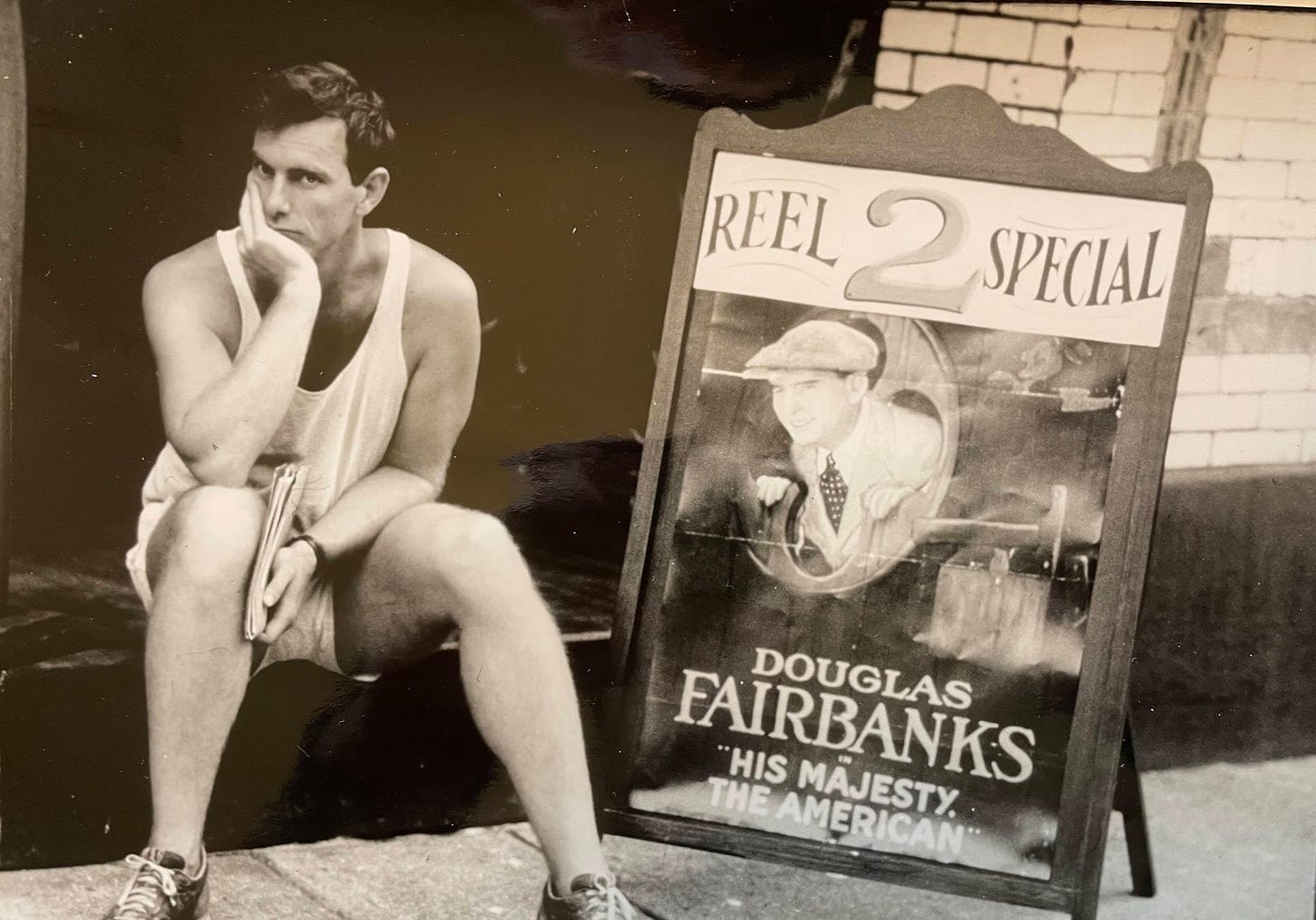

Sayles, 37, is 6 feet 6 and must weigh around 225 pounds. He looks more like a veteran NFL tight end than a brainy author-screenwriter-director-actor. The Williams College graduate has figured out how to pick Hollywood’s wallet (by writing screenplays for such movies as “Alligator” and “The Howling”) while turning out his own self-financed, low-budget but generally critically blessed movies like “The Return of the Secaucus Seven” and “Brother From Another Planet.”

Despite a chilly breeze and low-50s temperatures, Sayles is wearing only dusty white shorts, a tank top, disintegrating size-14 running shoes, a watch and no socks. On his head is the same green ball cap he wore while directing “Matewan,” his current well-received release about a bloody 1920 coal miners’ strike in West Virginia.

Berry begins cracking balls at Cusack.

Whack. Whack. Whack.

Cusack looks like a hockey goalie caught in a nightmare. He lunges left and right, knocking down hard grounders, handling tough short-hops and spearing several hot liners dead in his palm. He boots a couple, but he hangs tough.

Berry hits about 30 balls in all. Cusack is sweating and panting but his dust-eating catch of a low liner to his left on take No. 8, one of several great plays, would have done Buck Weaver proud. Even Brooks Robinson.

Sayles also is pleased. He’s played enough baseball to know that it’ll look just as genuine on film.

But Cusack’s slick fielding doesn’t merely satiate a jock director’s desire for athletic authenticity. It also serves Sayles’ sophisticated dramatic purposes.

As captured by the camera of director of photography Bob Richardson (“Platoon”), Cusack’s catch will clearly show to the audience that it was unfair for Buck Weaver to have been banished from baseball for life.

For despite his ground-floor involvement in the fix, Weaver played his heart out in the Series. It was so obvious to his seven co-fixers that he played to win that they never gave him a dime of the $80,000 that Asinof says the gamblers paid them.

All this effort expended for what will amount to maybe 10 seconds of screen time is indicative of Sayles’ efforts to make “Eight Men Out” rise above the typical sports movie, most of which are as short on sports realism as they are long on bubble gum-card heroics, one-dimensional characters and clunky drama.

“Eight Men Out,” like “Matewan,” is one of Sayles’ “dream projects.” Though he’s greatly amended it since, Sayles wrote a sample screenplay adapted from Asinof’s book 11 years ago, when he made the decision to go from novelist to screenwriter. He used the script, successfully, to prove to agents that he could handle a complicated story.

In addition to the tangle of good old human corruption, greed and tragedy, Sayles will re-enact dozens of crucial plays of the nine-game series that the Reds won five games to three. Which is why he hired Berry as a coach/adviser and why he picked a roster of actors who can play and players who can act.

After shooting exteriors in Cincinnati in late September, “Eight Men Out,” from the hot producing duo of Sarah Pillsbury and Midge Sanford (“Desperately Seeking Susan,” “River’s Edge”), moved into Bush Stadium for five weeks.

The 135 cast and crew members occupy 100 hotel rooms at the Riverpointe Hotel, a former HUD low-income housing project located a few miles east of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in a part-park, part-residential, part-industrial cityscape as flat as a basketball court.

Its two 12-story towers--what producer Sanford jokingly refers to as “our own little Century City"--have been renovated into a pleasant but Spartan hotel and apartment complex that’ll be headquarters until filming ends Nov. 17.

From the Riverpointe, Bush Stadium’s light standards can be seen on the other side of the tree-lined White River. The unmodern look and relative adaptability of the stadium, which was built in 1931 and seats 12,500, is what brought her Black Sox Inc. production company to Indianapolis, says Sanford, sitting at a table in the Reds locker room beneath the stands to escape the chill outside.

Shortly after she and Pillsbury optioned the rights to Asinof’s book in 1980, she says, Sayles got wind of it and called to express his interest.

Sayles was the subject of so much good Hollywood buzz back then that they thought they’d “instantly get a deal,” Sanford says. But though many male studio chiefs loved baseball and were familiar with Asinof’s book, it had four strikes against it.

“It was a period piece,” says Sanford, ticking them off, “and therefore too expensive. It was about baseball--which limits its market. It’s an ensemble piece--and they wanted star vehicles. And it had a downer ending.”

So as Sayles reworked the script in between his other projects, Sanford and Pillsbury put together new packages built around name actors that at various times included Tom Cruise, Emilio Estevez and Kevin Bacon. It wasn’t until last year, she says, that an independent financing deal was finally worked out.

Sanford sees the irony in the fact that a movie about baseball is being worked by a crew that’s 50 percent female and is being produced by four women (including co-producer/production manager Peggy Rajski and executive producer Barbara Boyle).

A Sarah Lawrence College graduate and former elementary school teacher, the 40ish Sanford doesn’t hide the fact that the movie is a non-union production--another sweet irony, considering Sayles’ ardent pro-labor politics, which are so evident in “Matewan.”

“It couldn’t have been made without being non-union,” she says firmly.

The biggest expense is in creating the period look, she says. Thousands of extras are needed. And making Bush Stadium look like Redland Park--and then tearing down the outfield walls to make it look like Chicago’s Comiskey Park--is a major cost incurred by production designer Nora Chavooshian’s art department.

(According to prop man Kirk Corwin, Rawlings donated baseballs with the old-time red-and-black stitching and Hillerich & Bradsby, which keeps files on every Louisville Slugger it’s ever made, donated duplicates of 60 bats used by players from the era. Old catcher’s gear was rented and so were 18 period mitts, which were so fragile they had to be reinforced by a leathersmith, who also made six new gloves using Sox second baseman Eddie Collins’ ancient original as a pattern.)

The producers and Sayles are getting paid less than they would on a bigger-budgeted movie, says Sanford, and “all the actors are working for SAG scale ($1,319 per week with a $42 per diem). This is an ensemble movie. There’s a spirit of this movie. It’s a team. It’s an independent low-budget movie and no one is going to be treated differently from anyone else. Actually,” she laughs, “the line is, ‘Everyone will be treated equally as poorly.’

“In dealing with the agents, we really had to explain this over and over again. Their attitude is, ‘If my client takes this movie for a certain fee, it’ll be difficult to get market value next time.’

“But the name actors feel pretty passionate about doing this. Some of them could make a lot more money than they’re making on this movie. Who knows what they are giving up?”

John Sayles’ Social Conscience

The infield is in shadow. A long Saturday’s shooting is done and the crew is packing up equipment. Sayles walks into right field to seek some sunshine, but the weak rays offer only psychological relief from the low-40s chill.

Over the P.A. system, a voice is announcing the winning numbers for the $5,000 in raffle prizes, part of the bait used to lure 5,000 extras to Bush Stadium for crowd scenes. Despite a lot of local media attention, though, fewer than 1,000 showed up, which meant that Sayles had to waste a lot of time moving people around in the stands all day.

But such logistical problems hasn’t eroded the saintly unflappableness that appears to be his modus operandi on the set. He doesn’t seem tired or annoyed, and he looks just as relaxed when he views the dailies after dinner in the basement of the Riverpointe.

Squinting back toward the emptying infield, he praises the baseball prowess of his young Hollywood all-stars--Cusack, Sheen and Sweeney--without forgetting old pal Strathairn.

He wishes the movie weren’t such a big project. “It’s too much. The more variables you have, the less of your day is about acting. The less is about shooting, and the more of it is about logistics.”

He explains how a more corporate America has gone from being a baseball country to a football country, and how the pastoral game of baseball at the time of the Black Sox scandal already was being encroached upon by the modern world.

Sayles knows the bad rep of Hollywood sports movies, and numbers “North Dallas 40’s” football and “Drive, He Said’s” basketball among the few movies whose sports sequences he’s found convincing.

A Schenectady, N.Y., kid who grew up a Pittsburgh Pirates fan and claims he learned everything about style from the great outfielder Roberto Clemente (“He always played hard . . . and looked good even when he was swinging at bad balls”), Sayles puts to rest any idea that “Eight Men Out” is just a simple baseball story about eight guys who sold their souls.

The director’s social conscience is as active as ever. He sees “Eight Men Out” as a story about how people are corrupted bit by bit. “It’s about a fix and about how these guys kind of corrupt each other. But they are also corrupted by the outside.

“It’s what ‘The Natural'--the book, not the movie--was about. Something that’s kind of natural and pure, and you just go out there and play and it’s kind of fun, and how that commercialism and outside world comes in and turns it into something else. How money can really destroy something.

“But on the other hand,” he says after pausing to autograph a baseball for a movie fan, “when you get into the story of this thing, it’s really about corporate America.

“It wasn’t even corporate yet. It was really entrepreneurial, old-fashioned, capitalist America. It’s a labor situation. Sort of like ‘Matewan’ in a way. These guys are owned. The owners are owners. If you got hurt, there was no pension, no nothing. There was no Social Security. You were just gone. You were in Pawtucket the next week. So everybody else was just trying to make what they could when they could.”

Charlie Sheen and new pal D. B. Sweeney (they teamed on the just-released cop-and-car-thief flick “No Man’s Land”) are in their Sox uniforms playing catch (with their modern gloves) along the left field foul line.

Nearby, a dozen others are also taking full advantage of Bush Stadium’s grassy expanse to beat the usual boredom that afflicts a movie set.

Michael Rooker, a rowdy, fun-seeking Chicago actor cast as first basemen Chick Gandil, is fungo-ing fly balls deep into right-center field, where off-duty actor Richard Edson (“Stranger Than Paradise”) and Sweeney’s visiting younger brother Tom are among those taking turns shagging them.

Sheen, a mature-looking 22, looks more natural in a baseball uniform than in the jungle fatigues he wore as Vietnam grunt Chris Taylor in “Platoon.” He’s a cool-guy type who patiently endured the assaults of autograph-seeking extras who surrounded him at lunch the day before.

It isn’t noticeable as he snaps up one of Sweeney’s throws, but the former shortstop and pitcher at Santa Monica High School may need an operation to repair his left shoulder, which he says he injured “chasing a curve ball” while taking “BP” (batting practice) with the Dodgers this summer as part of his preparation for the movie.

Sheen plays outfielder Oscar (Happy) Felsch. It’s a minor role, but he is pysched about being able to do a baseball movie.

“I heard about it through my brother Emilio (Estevez), who had a problem with his schedule. He was really depressed because he really wanted to do it. He’s a good ball player, too--yeah, he can swing a bat.

“This isn’t really a career move,” Sheen explains, rifling a throw to Sweeney. “I have, like, three scenes and I’m just one of the guys. But it’s a chance to play in the World Series. It’s something I always wanted to do.”

Shoeless Joe Sweeney

D. B. Sweeney’s role is much bigger. He’s left fielder Shoeless Joe Jackson, the illiterate South Carolinian whose .356 lifetime batting average is the third best of all time behind Ty Cobb and Rogers Hornsby.

Jackson was a certified superstar getting paid $6,000 a year by ultra-penurious White Sox owner Charles Comiskey--while players on other teams with half his talent were getting $10,000. Jackson accepted $5,000 of the gamblers’ money but apparently--like teammate Buck Weaver--did little to help the losing cause: He hit .375 with 12 hits in the Series.

Sweeney, 26, is a natural right-handed hitter but had to learn to hit leftie to portray Shoeless Joe. It wasn’t too hard. He’s an excellent player whose promising collegiate career at Tulane was aborted by a motorcycle accident that ripped up his knee, left him unable to run at full speed for 18 months--and gave him time to explore acting.

A Long Island boy (but a Red Sox fan) who’s been traveling to L.A. enough to have become a regular fixture on the softball diamonds of the San Fernando Valley, he says his research included going to just about every ballgame he could plus a trip to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y. He even started collecting baseball cards again.

“It wasn’t because I, like, had this slavish dedication to my craft, or anything like that,” he says. “It was, like, fun. A fantasy--to hit a home run in the World Series. It wasn’t about me feeling like I owed anything to my discipline. It was fun.”

Son of a history professor, Sweeney is as eager to talk about the Bork confirmation hearings and the role of the Supreme Court as he is to clown around for the video cameras of a visiting production crew from sports channel ESPN or hold long talks with Sports Illustrated baseball writer Steve Wulf.

But he’s not afraid to let off a little steam. The previous weekend, he had driven the early ‘70s MG he’d recently bought up to South Bend to see a Notre Dame football game. On the way back, he took too ample advantage of the new speed limits and blew the $2,000 car’s engine. He was seriously trying to whip up a short film starring the now-hated sports car, which he wanted to blow to bits at the end.

“Charlie and I are both here--I risk going out on a limb and speaking for Charlie--first, because it’s a wonderful script about baseball. I think Charlie had some of the same experiences about baseball as I had, about wanting to be a ballplayer, and acting being sort of a second choice.”

But Sayles as the director was a powerful inducement too, he says, shifting the wad of licorice in his mouth to the other cheek (real chewing tobacco was found to be far too foul-tasting). “I know for me that’s one of the big reasons I’m doing it. If we had some English director doing it, I don’t know if I’d be here,” he says, before quickly adding with a smile, “I think I’d be here anyway.”

John Cusack, friendly and naturally photogenic in the leather jacket he constantly wears over his Sox uniform, echoes Sweeney’s praise of Sayles.

“It’s good to know you’re working with a film maker who’s going to make you look good,” Cusack says from behind a pile of clams and several desserts during lunch under the stands.

“A lot of times, you get to the point where you’re watching your own ass, making sure your performance is good. He’s making everybody look great, and even if you don’t agree with him or think you need another take, all you need to do is look at ‘Matewan’ and his other films and you’ll know there’s not a bad performance in any of them. So you’ve got to trust him, got to trust his taste--and I do.

“He’s a smart dude.”

Local Boys Make Good

Sayles is impersonating a pitching machine. Wearing a baseball glove and sitting on the ground next to a plywood-shielded movie camera 10 feet from home plate, he flips pitch after pitch to Gordon Clapp, who plays Ray Schalk, the hard-nosed White Sox catcher, who wasn’t in on the fix.

Clapp would later be filmed sliding in safely head-first under the tag of Reds second baseman Maurice Rath, played by an extra, Larry Oliver, 43, of Indianapolis.

Oliver and the rest of the 1919 Cincinnati Reds are off-camera, over by their dugout, playing catch or just hanging around looking spiffy in their fancy red-and-gray--and number-less--uniforms.

The Reds are one of four fully uniformed teams of extras formed from among about 160 local softball and baseball players who attended tryouts. The other teams are the St. Louis Browns (for the game when the Sox clinch the American League pennant) and semi-pro teams from Hoboken and Hackensack. (Shoeless Joe will be shown playing in the bush leagues under aliases in the decade following the scandal.)

Oliver is a former semi-pro baseball player who took a leave of absence from his job as a data processor for the IRS to be in the movie. He says his movie career has been “mostly standing around and watching. But it’s neat, really neat.”

He and his fellow Reds are each receiving $50 a day for 14 to 16 days that begin at 6 a.m. and end at 6:30 p.m. (Umps, like foundry worker Wayne Fox, get $20 per day, as do the 100 or so extras who sit in the stands each day; the masses of extras needed for big crowd scenes get $5 a day plus a chance to win Bingo and raffle prizes).

The Reds worked out six times together as a team under John Jackson, 36, a former scout in the Houston Astros organization who conducted the extras tryouts. Coach of the Indianapolis Arrows softball team, which Oliver and four other Reds play on, Jackson works for the U.S. Track and Field Athletics Congress.

In the movie, he’ll be a Reds base coach. But on the set Jackson acts as sort of the unofficial conscience of baseball. He sticks close to Berry and carries around photocopies of the box scores of the 1919 Series. He seems to have memorized Asinof’s book, which he considers one of the two best books on baseball he’s ever read. James Michener’s “Sports in America” is the other.

He’s pleased by Sayles’ attention to fact. Why is he so concerned with accuracy? “Most people who go to see this movie will be baseball fans and one of the things they’re going to look for is inaccuracies. So the closer we stay to the story, the better baseball movie it will be.”

It’s hard to tell if he’s only kidding when he says he loves baseball more than he loves his wife. But it’s certain he’s thrilled to be so immersed in a baseball movie. As he quips whenever he gets the chance, “I never made it to the Series with Houston, so this is my one shot--even if it is fixed.”

Ken Berry, 46, says the two greatest moments of his major-league career were winning two Gold Gloves and singing “Proud Mary” in front of 3,000 tuxedoed sports people at an Angels-Dodgers sports banquet.

A career .255 hitter and an excellent fielder with the White Sox, Angels and Brewers, he holds the American League outfield record for most consecutive chances accepted without an error (510 over 211 games). He now works in the Kansas City Royals minor-league organization as a hitting instructor and hopes to get back into the majors as a coach.

His baseball experience was mostly a good one, he says, and he’s not at all bitter about his salary or envious of today’s wealthy ballplayers (who average better than $400,000 a year).

“I don’t feel sorry for the owners one bit,” he says. “They suppressed salaries for so long that when it exploded, a .230 hitter started making $300,000. Well, it’s not his fault.”

The most Berry ever earned was $48,000--twice with the Angels--but he gets a kick out pointing out that his first-year salary in 1965 was only $8,000, 46 inflationary years after first-baseman Chick Gandil decided to throw the 1919 series in part because he was making only $4,000.

Before filming stared, he conducted three weeks of basic spring-training-type workouts with the actors--everything from running and stretching exercises to batting practice. It wasn’t too tough coaching a few actors, though. He’s used to working with 110 players in spring training camps for teams like the Mets.

He can talk for an hour about the subtle mechanics of hitting and fielding. Patient, low-key and vigilant in his role as reality expert to Sayles, Berry is the one who’s called on to hit hard liners at Cusack or make hard throws from off-camera that are timed to just nip batters at first base.

Surprisingly, though Berry has high praise for Cusack, Sheen and Sweeney’s baseball skills, he ranks David Strathairn (the sheriff in “Matewan” who’s cast as Sox pitching ace Eddie Cicotte, who deliberately lost two Series games) as the best natural athlete among the actors. “If you picked out one guy who could do just about everything, he’s the guy. Yet he never played past high school. He’s really got a lot on the ball--he can catch, he can run and he’s a good-looking batter.”

Of his actor/players, whom he always addresses by their baseball names, he says: “These guys are--like anybody else who gets in the game--a little ego-oriented and they want to hit the ball out of the park. We’re not here to hit it out of the park. We’re here to hit it hard.”

After he finishes “Eight Men Out,” Sayles plans to return to writing fiction for about a year, as well as the occasional for-hire screenplay. As for his own films, “I’ve got some vague ideas, but I think they’ll be smaller, more contemporary movies. Some day I’m sure I’ll do a movie with basketball in it. That’s really the game I’m most familiar with and still play.”

Basketball is actually Sayles’ game. He played in high school--he was a varsity four-letter man (football, baseball and track too)--and he can be seen on the court in the basketball scenes in “Return of the Secaucus Seven.”

Thus it was with some trepidation that a reporter tells Sayles of the only criticism of him of any kind heard on the set in three days.

According to the otherwise admiring Cusack, who had been in several pick-up basketball games with Sayles, the director played well on offense--he could shoot from outside and was hard to block out under the boards. But Cusack reported that “Sayles played no D"--no defense.

Sayles retreats a half-step from the blow of such serious slander.

“No D?” he yowls (smiling broadly but unable to hide the hurt). “I had already played about five one-on-one games before he showed up, and I wasn’t about to play any D with the light going down!”

With its big stars, ambitious production values and--for him--big budget, “Eight Men Out,” Sayles says with a laugh, is “probably the pinnacle” of his Hollywood career: “It’s all downhill from here.”

He’s not going Hollywood, though: “I went Hollywood and I came back. I went as far Hollywood as I’m ever gonna go, I think.”