The annual baseball edition -- starring 'Eight Men Out', Vin Scully and fricking Tommy Lasorda

To mark the coming of another season of our former national pastime, here is an instant replay of my feature on the lovable XXX-rated Dodgers manager who died Jan. 7, 2021.

Several other only slightly scuffed-by-time articles in my MLB collection from the 1980s — a 1987 “Eight Men Out” location piece for the LA Times Sunday Calendar section, my anti-Little League rant for the Times opinion page and my Q&A with Dodgers announcer Vin Scully. Finally, there’s a 2002 interview with pundit George Will about his favorite American game.

*****

Hanging out with Tommy Lasorda

In 1986 I was lucky to hang out before two games with the LA Dodgers manager in his office under Dodger Stadium. This is the X-rated version of my unforgettable adventure.

Dodger Stadium, Spring, 1986

“I get these fucking invitations to weddings,” Tommy Lasorda was saying, his bare feet propped on his desk in his office deep beneath the sunny stands of Dodger Stadium. “I don’t know who these fucking people are.”

The celebrity Dodgers manager — dressed only in his white cotton underwear and opening his mail prior to a Saturday night game against the Giants — wasn’t complaining.

Throwing f-bombs was just the way the jolly goodwill ambassador of baseball and former TV lasagna salesman talked when he wasn’t appearing on “The Tonight Show” with Johnny Carson show or attending black-tie dinner dances with the Reagans at the White House.

It was early in the 1986 season — one of the worst in Lasorda’s 21-year managing career. The Mets were going to win their second World Series. The Dodgers’ Fernando Valenzuela was the NL’s top pitcher, but LA was going to finish sixth in the NL West, 16 games under .500.

Lasorda, who died January 7 at age 93, was already a cinch for the Baseball Hall of Fame — as a coach, not a player. Before taking over the Dodgers in 1977, he spent 11 years as a minor league pitcher, four as a scout, eight as a minor-league manager and four years as a Dodgers coach. As a major leaguer he was a total bust — a pitiful 0-4 in two years with the Dodgers and Kansas City.

But in his first nine years as manager he had already guided the Dodgers to three league championships and three World Series, including a 1981 series victory over the Yankees. By the time a heart attack would force him to retire in 1996, his teams would win two World Series, four NL pennants and eight division titles. He waltzed into the Hall of Fame in 1997.

I had access to Lasorda’s famous bunker for two weekend games because I was doing a freelance piece on him for an airline magazine. For all his bluster, Lasorda couldn’t have been nicer or more welcoming. He treated me like he had known me all my life, called me “Billy” and made no effort to dial down his hyper persona or clean up his foul language because a strange journalist with a tape recorder had invaded his inner sanctum.

Lined with pictures of the Blessed Mother, big league politicians and Hollywood superstars, Lasorda’s office used to crawl before game time with his big-time pals. Frank Sinatra, Bob Hope, Carson and other rich-and-famous LA folk would regularly drop by to partake of the free booze, beer and food LA’s trendiest restaurants were always sending over.

But all that celebrity fun stuff had abruptly ended earlier that week when the new party-killing MLB Commissioner, Peter Ueberroth, put baseball’s locker rooms and clubhouses off-limits to celebrities, cronies and various other riff-raff.

Only the working press was allowed to enjoy Lasorda’s entertaining stream of baseball stories, playful ragging and spectacularly crude but somehow endearing vocabulary.

The baseball public at large was spared knowledge of Lasorda’s X-rated tongue, but every major league city sports writer in baseball knew all about it. Many of them had dubbed their own copy of what was commonly known as “The Kingman Tape.”

One of several Lasorda tirades bootlegged around baseball, the Kingman audio contained Tommy’s hilarious 30-second rant in response to an innocent but stupid post-game question asked by a radio station sports reporter in 1978.

The reporter had asked Lasorda if he thought Dave Kingman – the Chicago Cub slugger who had just tortured the Dodgers by hitting three home runs and driving in eight runs — had a good day. An angry string of obscenities followed.

Absent the celebrities, the episode of the “Tommy Lasorda Pre-Game Show” I saw was fairly typical. Coaches and players like Steve Sax and Fernando Valenzuela wandered in and out. Lasorda spoke to them in English or Spanish. Dodger play-by-play man Vin Scully and former L.A. Raiders star running back Marcus Allen dropped by. The Republican governor of California, George Deukmejian, called to talk baseball.

As two bored baseball beat writers slouched on the couch watching the Atlanta Braves game on the big screen TV, Lasorda sat behind his desk reading his mail aloud and keeping an eye on the game. Peering over the top of his reading glasses, he joked and argued baseball. When Dale Murphy missed an inside fastball in the Atlanta game, he sniped, “He can’t hit that fucking ball inside.”

While Lasorda was telling everyone that Murphy was real prick as a person until manager Chuck Tanner straightened him out, someone came in and handed him a sheaf of computer paper.

“We get more fucking papers, a computer, all these fucking averages. These are yesterday’s. People want to know if we ever had a computer in the dugout. Yeah, we tried it, a couple years ago. We’d feed it all the information we could get and whenever we got in a jam it would say, ‘Fire the manager.’ It kept coming out with the same answer — ‘Fire the manager’ — so we got rid of that fucking computer.”

You’d never know from Lasorda’s nonstop cheery babble that the Dodgers were struggling through their first home stand. Or that the season had started with slugger Pedro Guerrero lost for three months with a crippling injury. Or that the day before Lasorda had arrived at 2:30 p.m. for a 7 p.m. game and had not left Dodger Stadium until 12:15 in the morning.

When the clubhouse boy appeared at the door carrying a clean pair of mid-thigh-length athletic underwear, Lasorda — still talking — half stood behind his desk, yanked down his underpants and threw them to the boy as the boy threw a fresh pair to him.

Catching the pants, pulling them on and sitting down again without a flash of rounded 58-year-old flesh or self-consciousness, Lasorda said he got a hundred letters a week from Dodgers fans. They ask for autographs or invite him to come to their weddings or their kids’ bar mitzvahs and baptisms. He rarely shows up, but he responds to each letter in some fashion, even licking the envelopes himself.

The first afternoon I was there Lasorda read a letter out loud from a fan asking if he would call his dad, who was a loyal Dodgers fan and was dying of cancer. Lasorda immediately dialed up the hospital, but the line was busy. Then he read a letter from a devout Dodgers fan in LA who invited him to his wedding.

Lasorda checked the schedule and saw the Dodgers were going to be in Montreal that day. “I’ll have to write and tell him I’d love to be there, but I can’t. I’m going to say, ‘Why the hell didn’t you check the schedule, if you’re such a Dodger fan?’ I said that to the president one time.”

“Which president?” a sports writer said.

“Calvin Coolidge, you cocksucker,” Lasorda said with a hearty laugh before proceeding to spin a long story about how President Reagan had checked the Dodgers schedule first before inviting him and his wife Jo to a State Department dinner-dance in Washington.

All of which apparently reminded Lasorda of another story. “You will not believe this fucking story,” he began.

“I get a letter with an invitation to a wedding from a couple in Florida. They live in Pensacola and they said they were coming out here to Los Angeles to get married in Irvine and they’d like me to come to the wedding. I tell them I can’t make it because I have to go to Vegas to speak.

“So I get up in the morning and I go to the Orange County Airport, the John Wayne Airport, to fly to San Francisco and people are asking for my autograph. So this young couple comes up and asks me for my autograph. So we fly to San Francisco and as we’re waiting for our luggage at the airport the couple tells me they just got married.

“I said, ‘Where are you going?’ and they said, ‘We’re going down to a hotel and we’re going to spend a couple days here.’ I said, ‘Why don’t you ride with me? I’m going to town and it won’t cost you anything?

“All the sudden they start telling me about just getting married and I go, ‘Wait a minute. Did you get married in Irvine? Near Newport Beach?”

“They said, ‘Yeah.’

“I said, ‘I got an invitation to your wedding.’

“Then the guy goes to his wife, ‘That’s right. I remember when your mother said that because we love the Dodgers so much she’s going to invite Tommy Lasorda to our wedding.’

“And I’m in the fucking cab with those people! That’s the same fucking couple!” Lasorda yells, banging his desktop, “that the mother writes to invite me to the fucking wedding in Newport Beach! They didn’t know that the mother had sent me the invitation. Can you believe they’re going to go home and say that I was in the fucking cab with them?’

“What are the fucking odds on that? It’s unbelievable. But there’s always unbelievable stories.

“Like that time when Frank Pulli is umpiring behind the plate. Do you know how (Dodgers pitcher) Jerry Reuss likes to fuck around? So Reuss took a baseball and he wrote on it, ‘Dear Frank, God bless you. Your friend, Tommy Lasorda’ and he gives it to the ball boy – you know, the kid who usually brings new balls up to the fucking umpire. This is the eighth inning.

“In the fucking top of the ninth we don’t hear anything from Frank Pulli, so we figure the fucker didn’t see the ball. Now the fucking game is over and I forgot about it.

“So we come in and (Dodgers relief pitcher) Tom Niedenfuer walks over and says, ‘You won’t believe what I saw.’

“I said, ‘What?’

“ ‘In the fucking ninth, I had a fucking ball and I looked down and I found writing on it.’

“I said, ‘No kidding. What did it say?’

“ ‘Dear Frank, God bless you. Your friend, Tommy Lasorda.’ ”

“I said, ‘Then the umpire didn’t see it. What happened?’

“Niedenfuer said, ‘The guy fouled the fucking ball off.’

“So I said, ‘End of the fucking story,’ right?

“I go upstairs and meet my wife and she said, ‘You won’t believe what happened.’

“ ‘What?’ ”

“ ‘A foul ball hit right next to me.’ I said, ‘Oh, is that right? What the fuck do I give a shit about a foul ball?’

“She said, ‘The guy behind me catches the foul ball and it’s got writing on it.’

“I said, “Oh God! Here comes that fucking ball again! What did it say?’

“ ‘It said, ‘Dear Frank. God bless you. Your friend, Tommy Lasorda.’

“I said, ‘So that’s where that fucking ball wound up!’

“She says, ‘You won’t believe the name of the guy that caught the fucking ball.’

“I said, ‘What?’

“ ‘Frank!!’

“Frank caught the fucking ball! Now what are the fucking odds of that? It’s fucking unbelievable!!”

“You think you’d say, ‘Well, the fucking guy makes up a story like that.’ But it’s just as unbelievable as that couple being in the fucking cab with me in San Francisco.”

“We’re supposed to believe that?” a sports writer asked.

“That’s as true as God made apples,” Lasorda assured him.

*********

As game time neared the newspaper guys drifted away. I was left alone in the office with Lasorda. He was no longer ripping open his mail and stuffing autographed photos of himself or his star players into mailing envelopes.

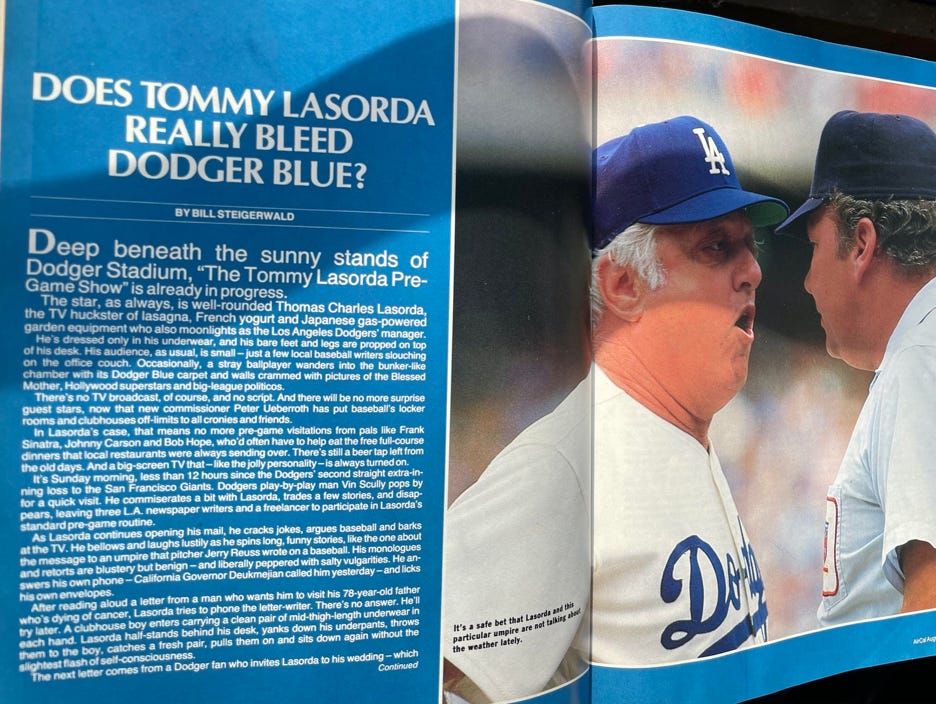

The Tommy Lasorda Pregame Show was over. He was subdued, almost serious. As he answered my questions he began pulling-on parts of his beloved Dodger Blue uniform — the one he said he hoped to die in.

“I always had a dream of being the manager of the Dodgers,” he said. “The Dodgers have been great to me. Mr. (Walter) O’Malley gave me my start in baseball. I’d never go anywhere else as long as they want me to stay around here.”

He credited his success to his players and coaches -- “the greatest staff any man could ask for” — and the full support of team owners and management. Lasorda said he never regretted a single day of the 37 years he had already spent in the Dodgers organization.

“You’re looking at the happiest most grateful man in the world. When I tell everyone how much I love the Dodgers, a lot of people think I’m full of baloney. But they don’t realize how true it is and how much I mean it. I work for the greatest organization in the world, without a doubt.”

He said he enjoyed every aspect of his job and to anyone observing him for more than 10 minutes it was obvious he was telling the truth.

For instance, before the game on Saturday the Dodgers PR person stuck his head in the office and asked him to speak to a high school baseball team from Connecticut that was out on the West Coast for a tournament. Lasorda gladly obliged.

Stepping into the hallway just outside the Dodgers locker room, he dazzled the young ballplayers and their equally awestruck coaches with a mini-version of the pep talk/stand-up routine he’d delivered at hundreds of baseball clinics around the country.

Contented players, Lasorda told them, play better. That’s why he tried to create a family-like attitude and an atmosphere on his teams where everyone pulls together. “I tell my players that individualism wins trophies and teamwork wins championships.”

He urged sluggers to be happy bunters if that was what their coach ordered. “If you all execute the fundamentals and play unselfishly, you’ll be tough to beat. Just remember one thing,” he said in closing, “when things get tough, rely on the Italians.”

Lasorda not only left each of those kids with a memory of a lifetime, he left them laughing.

Laughter, he firmly believed, was “food for the soul” and all the pregame frivolity and boyish good fun that swirled around him in his office was no accident. “I like to build a family-type team because if you’re part of the family you’ll try to be happy, to be together, to love each other. I like to see the guys enjoy each other before the game.”

So when does he pull out the whip? “If I thought they were neglecting their jobs, it doesn’t matter if they’re having fun or not, I tell them about it. When it’s time to get between those two white lines, it’s a different story.”

The most important function of a manager, he said, is to “extract every ounce of ability out of each player. And everybody in the country, from the president on down, sometime or another in their life needs to be motivated. Needs to be convinced that they can do better than they’re actually doing. A lot of times a lot of us feel we’re doing our best, but in reality we aren’t.

“People say to me, ‘You you mean to tell me you’ve got to motivate a guy making $800,000 and $1 million a year?’ I say, ‘Absolutely. Everybody. Everybody.’ ”

A player once asked Lasorda if he was accusing him of not trying hard enough. “I said, ‘Buster, let me tell you something: I can get truck drivers and mailmen to try. You don’t win championships with triers. You win with doers.”

Lasorda said he didn’t like to compare eras. Today’s players got more money, but he didn’t think they were spoiled. And he hated to list his favorite players, because it was like trying to choose which fingers he liked best. Anyway, he said, there would be 20 or 30 of them.

Lasorda loved his players like sons. When he first became a manager in the minors he had more in mind than developing future stars for the Dodgers. His ultimate goal was to assure the parents of his players that their son was playing for a man who was just as concerned with how they acted off the baseball field as with how they performed on it.

“I made them go to their churches. I made them write home to their parents. I really got close to these guys — I loved them. I met their parents. Knew their families. And I said to myself, ‘I don’t think I could ever be that close to a ballplayer again, because these guys played for me in the minors.’ ”

Little did he realize, he said, that there was going to come along the Mike Scioscias and the Steve Saxes and the Fernando Valenzuelas and the Greg Brocks and … Lasorda named virtually every player on his current roster.

Pulling on his Dodgers socks, Lasorda said major league baseball players have more of an impact on the youth of our country than anybody. He said his players – all pro athletes – should spend more time convincing youngsters to get a good education and teaching them about the evils of drugs.

“We want the people to have their sons look up to us, to say, “Hey, I’d love to be like Mike Scioscia. We don’t want them to be like Steve Howe, who got involved in illegal drugs. We don’t want kids to idolize those guys.”

I asked him if Babe Ruth’s drinking set a bad example for kids.

“Babe Ruth did no harm to anybody. Babe Ruth never broke a law. Babe Ruth went to visit kids in hospitals. Babe Ruth did everything he could to make a youngster happy. He never showed a disturbance amongst the public. Whenever he was among kids, did the kids love him? He couldn’t have been rude to them — he must have been a tremendous role model for kids. He was to me.”

Some illegal drugs are not harmful, I said, letting my hard-core libertarianism show.

“If they’re using drugs it certainly isn’t going to help them. It does absolutely no good to you. Does it make you a better hitter? Does it make you run faster? Does it make you better looking? Does it make you smarter? Then what the hell would they take ‘em for then?”

For recreational purposes? I dared.

“It’s against the law,” Lasorda said, stepping into his Dodgers pants and getting a little hot under his Dodgers T-shirt. “Why don’t they go out and steal cars for recreation? Both are against the law. Number 2, it’s a proven fact that it’s harmful to your body.”

So is booze, I said.

“But booze isn’t against the law…. To me, anyone who drinks and becomes an alcoholic, anybody who gets involved in illegal drugs, is weak. Medical people try to pass it off as being a sickness. I don’t believe it is a sickness. A sickness is when you’ve got cancer, leukemia, a bad heart.

“If you put all the wine my father drank in his life together, it’d flow over Niagara Falls for three weeks. But he worked every day. He had a family and was responsible. If my father drank and denied his family food, then he’s weak. But my father never did that. He never allowed a material thing to control him.”

What about the baseball media? I asked him if he ever got annoyed with them for harping on a controversy like the situation in the last game of the 1985 championship playoffs when Jack Clark of the Cardinals hit a home run to beat the Dodgers.

The Dodgers had a 5-4 lead with two outs and runners on second and third in the ninth inning, when Lasorda chose to pitch to Clark rather than have him walked intentionally to get to a less dangerous batter. But Clark hit a three-run home run, the Dodgers lost the playoffs and Lasorda was knocked around by the baseball press all winter long.

“Let me tell you something,” Lasorda said. “We are part of the great game of baseball and the great thing about the game is that everybody can second-guess.

“Don Shula is one of the greatest coaches who ever lived in football. He got beat by the New England Patriots in the playoffs. Do you read anything about how he had his cornerman in the wrong spot? That he played the wrong type of defense? Somebody says they play ‘a nickel defense, a dollar defense.’ Who knows?

“But everybody at one time or another has played baseball and they’re all able to second-guess. They can second-guess me about Clark. You know what I tell them after they said I should’ve walked him? ‘After he hit the home run my wife knows I should’ve walked him, and she don’t know one damn thing about the game of baseball. You’re no different than she is.’ ”

Niedenfuer was supposed to pitch Clark carefully with first base open but he didn’t, I said. It was his fault, but you got the blame.

“I want them to blame me. I didn’t blame Niedenfuer or the catcher. I put the blame on myself. I would rather them blame me than my players.

“Let me ask you,” Lasorda said, his hot temper showing for the only time in two days. “Do you think the Dodgers would send (LA Times sportswriter) Gordon Eades out to look at a prospect where he’s got $100,000 to spend?

“Do you think the Dodgers would ask a sportswriter to go down in the fucking minor leagues and check out a ballplayer down there to see whether they should bring him up or not?

“So how the fuck could he criticize me, who I’ve been in this fucking game a long fucking time? He can second-guess because anybody else can. Who in the fuck … Hey, I know what the fuck I should’ve done after it happens. Who the fuck don’t know that? Anybody who’s got any brains at all knows what you should’ve done after it happened.

“So that’s what makes our game so great, because people can do that. They don’t do that in football or basketball. That’s why it’s the greatest game in the world. That’s the thing you have to accept as a manager.

“But you know one thing? My bosses know what I do. The only people I really care about and who I want to believe I’m a good manager are (Dodgers executives) Fred Claire, Peter O’Malley, Al Campanis and my players.

“Did they have to tell Richard Burton he was a good actor? Check his bank account.”

fuckin' great column. Expurgating LaSorda would be like watering down great Chianti.