The night I ambushed the New Yorker's star global-warming alarmist

Elizabeth Kolbert came to Pittsburgh in 2008 to give a lecture about the threat man-made climate change posed to Earth. I cornered her afterwards. And I before that I wrote mean columns about her.

A global warming sermon

March 9, 2008

Elizabeth Kolbert of The New Yorker did not appreciate being ambushed by the local press.

But the superstar journalist, though wary, was a good sport when she was gently questioned by a fellow journalist in the nearly empty lobby of the Carnegie Music Hall in Oakland Monday night.

"Turnabout is fair play, I guess," she said to her interrogator, smiling but looking uncomfortable as she defended her well-known role as a global warming alarmist by saying humbly -- and disingenuously -- that she's not a scientist but merely a reporter who relies "on the consensus of the scientific community."

Kolbert had parachuted deep into Flyover Country to deliver a lecture/slide-show about global climate change to 960 Pittsburghers at the Drue Heinz Lectures series.

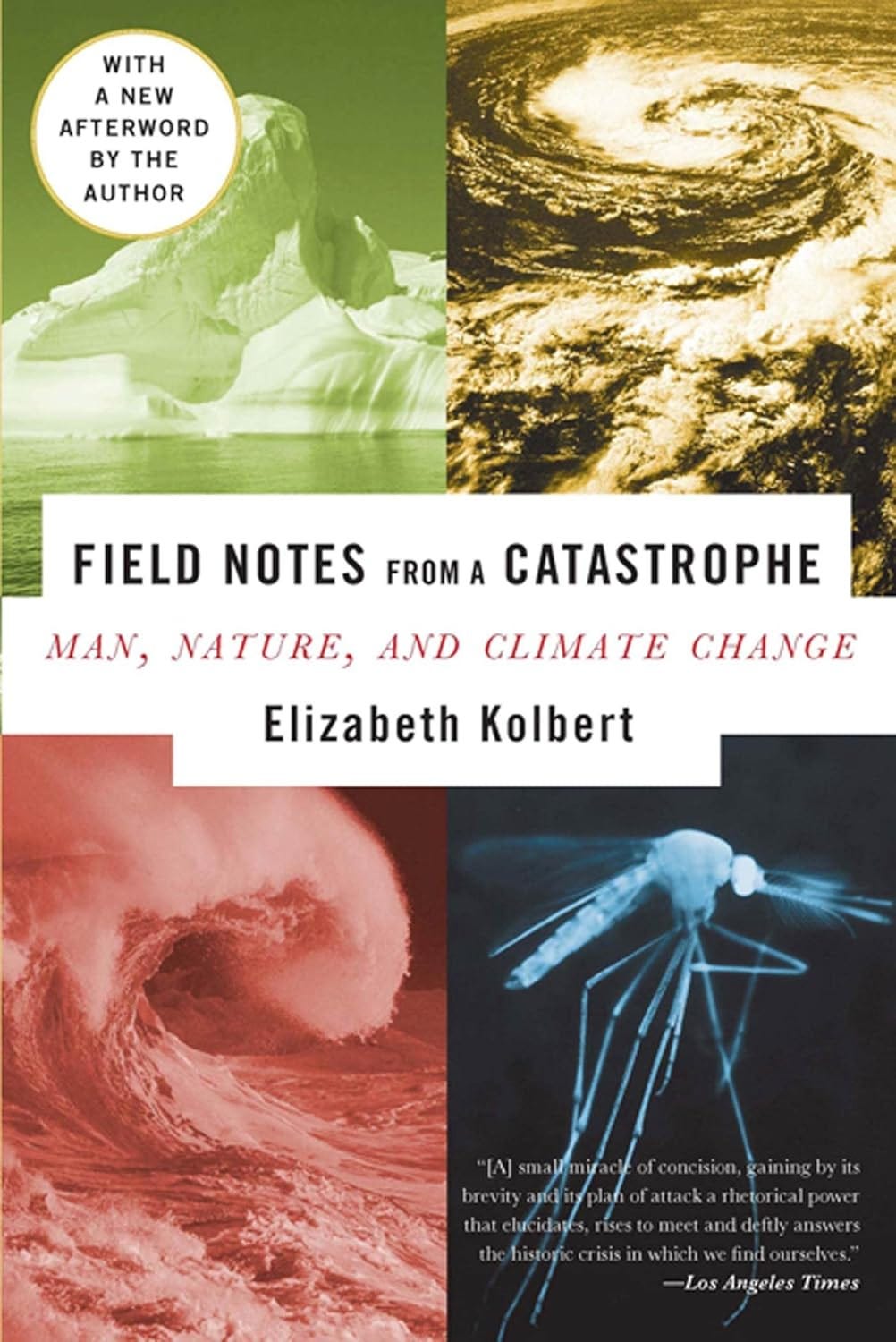

Her presentation was based on "The Climate of Man," the three-part, one-sided, epic magazine series she wrote for The New Yorker in the spring of 2005. Finely written and thoroughly reported, the series became the 2006 book "Field Notes From a Catastrophe: Man, Nature, and Climate Change."

The series, which won Kolbert lots of praise and awards from the environmentalist industry and its captive journalists, was really a protracted testimonial on behalf of the Al Gore Brand version of anthropogenic global warming.

Kolbert's Pittsburgh lecture stuck to the familiar alarmist story line. Though she promised her audience she'd present an unbiased account, Kolbert had no time for uncertainty or debate.

She used the usual photos of shrinking polar sea ice, upwardly angled temperature and CO2 charts and computer models to paint a grim scenario of unavoidable climate troubles ahead.

Shortly after Kolbert confessed to feeling guilty about the big carbon footprint she left in the sky by taking a plane to Pittsburgh, she did something surprising: She fessed up to reality and acknowledged that global warming was a humanly unsolvable problem.

She wished she had a 10-point plan to "get ourselves out of this mess," she said, but there are no easy answers.

"Just to stabilize the greenhouse gas composition in the atmosphere," she said, "we have to cut our current emissions by 60, 70, 80 percent."

"That's huge. It's going to take pretty much everything we've got, and then some," she said, ticking off such necessary remedies as conservation, land-use planning, a tax on carbon. Or "perhaps just making due with less -- living differently."

Kolbert concluded her lecture by dropping all pretense of being a fair-and-balanced journalist. Speaking as a mother and an inhabitant of Earth, she said it is morally unacceptable to just throw up our hands and not try to do something about global warming.

"It must be confronted in our individual lives, our communities and on Capitol Hill," she said, adding: "It seems to me that every single one of us should be thinking about this, thinking about what we can do, and then doing it. So I'm going to end tonight with a question for you, and that is, 'What exactly are we waiting for?' "

The applause that followed was genuine.

Sadly, however, no Pittsburghers seemed to notice they had heard only one side of an incredibly complicated debate. Not one of the 12 questions from the audience expressed any skepticism about any part of the global warming sermon they had heard.

My post-sermon Q&A with Elizabeth Kolbert

This is a copy of my ‘ambush’ interview of New Yorker magazine super-staffer Elizabeth Kolbert on March 3, 2007, in the lobby of Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Music Hall after she had signed her books and delivered a Drue Heinz Lecture.

Kolbert was the author of a spring 2005 series called "The Climate of Man," which I ripped in one of my columns as “an epic three-part harangue on how global warming is melting the Earth's polar ice cap and glaciers that didn't pretend to strive for balance.”

Her best-selling book, “Field Notes from a Catastrophe: Man, Nature, and Climate Change” (2006), grew out of her series. Based on several trips to the Greenland ice scheet, it was touted as a clear, unbiased, careful exploration of global warming firsthand and was declared “a book sure to be as influential as Rachel Carson’s ‘Silent Spring.’ ”

Kolbert has won a ton of major awards and is still as prolific as ever. This is how the New Yorker lists them.

Elizabeth Kolbert has been a staff writer at The New Yorker since 1999. Previously, she worked at the (New York) Times, where she wrote the Metro Matters column and served as the paper’s Albany bureau chief. Her three-part series on global warming, “The Climate of Man,” won the 2006 National Magazine Award for Public Interest. In 2010, she received the National Magazine Award for Reviews and Criticism. She is the editor of “The Best American Science and Nature Writing 2009” and the author of “The Prophet of Love: And Other Tales of Power and Deceit,” “Field Notes from a Catastrophe,” and “The Sixth Extinction,” for which she won the Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction in 2015. She received the Blake-Dodd Prize, from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, in 2017. Her latest book is “H Is for Hope.”

In 2008, Kolbert was as nice as she could be to me, despite being surprised by my stand-up interrogation.

Here’s the proof:

Q: I was disappointed …

A: Yeah.

Q: … that there was not a skeptical question asked in the question-and-answer session. I tried to raise one – I had my hand up.

A: Oh, sorry. (laughs)

Q: I’m somewhere between a fly on the wall and a columnist.

A: OK, OK.

Q: Is that normal that you don’t (have skeptical questions)?

A: As you know, if you give a speech, you attract a certain audience. I probably attract a certain audience.

Q: This is kind of a captive audience, though – the people who have signed up for this lecture series. If you were George Will (another scheduled speaker in the series), most of them would be here as well.

A: No I don’t think that they …

Q: There’s a certain … Well, I mean, I’ve covered this lecture series for a long time ….

A: OK, I don’t know if they’d be here .…

Q: I just wondered if that was normal (lack of skepticism).

A: I find increasingly few people who hold that view.

Q: Is there any event, any trend, any study, any – If James Hansen came out and said that he has been wrong for 20 years and in fact global warming was a natural phenomenon and not a man-driven one -- is there anything that would change your mind about what you have come to believe based on a lot of research and reporting?

A: It would take something like an IPCC report, saying, “You know, yeah. Now we’ve all changed our mind.” If that happened, I would certainly have to take a very serious look at that. I’m not a scientist.

Q: Nor am I.

A: … and I rely on the consensus of the scientific community.

Q: Exactly. The questions I was going to ask, if I had had the chance, are very simple.

A: Yes.

Q: You dropped the information that there might be a 20-foot rise in sea levels. You didn’t really say what would cause that …

A: If Greenland were to melt.

Q: You know how big Greenland is and how much of it is melting per year now?

A: That has been measured. Obviously, it’s a complicated figure, but yeah.

Q: It’s very, very tiny.

A: Yep, absolutely.

Q: You know what the average sea level rise is per century over the last many centuries -- 18 or 20 centuries, I guess. I mean, sea level has been going up; at one point it was 400 feet lower, when the last ice sheet was here. All that water was pulled out.

A: It’s hardly news to anyone, right.

Q: No. That’s right. My criticism of so much of our business – I’ve been in the business 30 years – I’m a friend of John Tierney’s – I don’t know if that makes me a friend of yours or an enemy.

A: I’d say not. But anybody is allowed to be friends with who ever they want (laughs).

Q: But my complaint about my profession, and yours, is the lack of perspective. You did it in your pieces. When you talked about Greenland and the possibility that it might melt, and I don’t know what the numbers were – let’s say that 56 cubic miles had melted as opposed to 36 cubic miles (some years before). Which is fine. But the perspective is that that’s 56 cubic miles of ice out of -- I think Greenland is 300,000 cubic miles of ice (Fact check: it’s almost 700,000 cubic miles). So we’re talking almost literally a drop in the ocean. That perspective is missing.

A: I think the pointt people make about Greenland – and once again it’s not my point – so it’s useless to argue with me …

Q: I’m not.

A: ... is that you have to be concerned that you are setting into motion processes that become self-reinforcing that could eventually – and I was careful in my book and in my series to say this will take hundreds, perhaps thousands of years – lead to the complete melting of the Greenland ice sheet. And that’s just a fact. I suspect that you have to be concerned ….

Q: And that would obviously take thousands of years.

A: No. It wouldn’t necessarily take thousands of years, but it would take a long time.

Q: As a journalist, you did a wonderful three-piece series; excellent, superior writing, great reporting; you went to a lot of fabulous places to report. But do you feel that you presented a fair and balanced – to use the Fox News term, um …

A: Yes, absolutely.

Q: … presentation of …

A: …Yes.

Q: … the global warming issue?

A: I spoke to dozens and dozens of scientists, and I represented what is usually called for lack of a better term “the consensus view.” It was the same view that was just presented by the fourth IPCC assessment, which represented the work of hundreds and hundreds of scientists and was vetted by governments all around the world.

So yes, I absolutely stand by it as a fair and balanced presentation.

*******

Before I met Kolbert in person, I wrote two mean columns about her and her climate change alarmism. I’m glad she hadn’t read them before I met her because she probably would have slugged me. One of them was when I caught her and the New Yorker — which was famed for its insane fact-checking process — making an embarrssing mistake about the speed of glaciers.

The New Yorker's false certitudes

Jan. 28, 2007

It's always fun to spot an embarrassing mistake in the haughty New Yorker.

But it's extra enjoyable when the error is made by Elizabeth Kolbert, the liberal-left magazine's official publicity agent for the Global Warming Apocalypse.

Glaring mistakes like the latest one Kolbert made Jan. 22 are extremely rare. The New Yorker -- winner of so many National Magazine Awards someone should call the Justice Department -- has always striven for perfect accuracy.

In fact, it has a fetish for facts.

Its vaunted battery of obsessive fact-checkers, now numbering 16, is legendary in journalism. But The New Yorker isn't nearly as infallible as it thinks it is. It's often caught being inaccurate or biased or both.

Just last week, conservative John Podhoretz pointed out on his National Review Online blog that Nicolas Lemann botched two important, easily verifiable facts about the Valerie Plame case in his Jan. 27 "Talk of the Town" item.

More serious is a defamation claim made in a 12-page letter by a Boston law firm on behalf of Chinese mathematician Dr. Shing-Tung Yau in connection with an Aug. 28, 2006, article. It demands a printed apology and alleges "egregious and actionable errors" and "shoddy journalism."

Speaking of which, crusader Kolbert's specialty is cranking out openly unfair and unbalanced articles on global warming like her epic "Climate of Man" trilogy in Spring 2005, which included a hilarious boo-boo that forced The New Yorker to do something it really hates -- admit a mistake and run a correction.

As part of her "proof" that the Arctic ice cap was rapidly melting, Kolbert wrote that the speed of a glacier in Greenland "had increased to 7.8 miles per hour" from its 1993 flow-rate of "three and a half miles per hour."

Kolbert meant 7.8 miles per year , which meant she was only off by a factor of 8,760. Unfortunately, her magazine's fact-checkers, editors and copy editors apparently were too busy cheering her on to spot her error.

Kolbert's latest gaffe can be found in her annoyingly critical Jan. 22 profile of Amory Lovins, the famous environmental genius and "natural capitalist" who, unlike Kolbert, prefers practical, pragmatic, market-driven solutions to energy conservation.

After confusingly toting up how many hundreds of billions Americans spend on gas, oil and energy each year, she concluded that "In 2007, total energy expenditures in the U.S. will come to more than a quadrillion dollars, or roughly a tenth of the country's gross domestic product."

Quadrillion?

Kolbert actually meant "a trillion dollars." And the annual U.S. GDP is about $13 trillion, not $10 quadrillion, as she implied. This time Kolbert was wrong by only a factor of 1,000.

No magazine -- not even a great one -- is perfect. Mistakes always will be made.

Kolbert's latest laugher is irrelevant compared to the junk journalism she practices in her global-warming propaganda pieces. And her mini-blunders only cause her magazine embarrassment because it foolishly sets itself up as infallible.

The New Yorker can continue to provide Kolbert with a soapbox to issue arrogant certitudes about the scientific causes and cures of global warming. It can produce all the egregiously liberal journalism it wants. It's still a free country.

But to avoid future ridicule, it might want to hire a few fact-checkers -- or editors -- who know how fast glaciers go, how big the U.S economy is and the difference between a trillion and a quadrillion.

Sunday, Jan. 15, 2006

Global warming agitprop

Bill Steigerwald

4–5 minutes

You'd think The New Yorker would practice fair-and-balanced journalism -- for its readers' sake, at least.

The elite weekly's readership -- disproportionately smart, wealthy and liberal -- includes many powerful people in the overlapping worlds of politics and media.

It's a good bet few of them faithfully devour National Review or Reason magazines. So if they are ever going to be confronted with "the other side" of an important, complex and overheated debate like global warming, they'll have to get it from The New Yorker.

Fat chance.

When The New Yorker last spring cranked out "The Climate of Man," an epic three-part harangue on how global warming is melting the Earth's polar ice cap and glaciers, it didn't pretend to strive for balance.

Elizabeth Kolbert, who has mounted a crusade to prove that global warming already is here and that industrial man is the chief culprit, wrote the series.

Most of the liberal mainstream media, of course, fawned over Kolbert's shameless exercise in scaremongering.

In an open letter to New Yorker Editor David Remnick, however, the late Jude Wanniski scolded Remnick for allowing Kolbert to produce such blatant faith-based agitprop. He called what Kolbert did "un-journalism."

Kolbert, who has since followed up with several smaller articles on climate change, is a global warming fundamentalist. For her there is no room for doubt or further research, much less honest debate.

The science already is indisputable. No chance computerized climate models are flawed. No chance natural, long-term global climate cycles are at work. Mother Earth is in dire peril. The only disbelievers are evil Exxon-slicked scientists or Bush administration yahoos.

As Wanniski predicted, the series, which will be released as the book "Field Notes from a Catastrophe" in the spring, probably will win a Pulitzer.

It's being compared favorably by the Religious Left to "Silent Spring," Rachel Carson's overwrought, scientifically challenged indictment of DDT that debuted in The New Yorker in 1962.

"The Climate of Man" already has won a big journalism award from the American Association for the Advancement of Science. It's nicely written. It contains The New Yorker's usual quota of trivial detail. It's 100 percent politically correct.

But it's not close to being fair-minded or intellectually honest, because, as Winniski knew, it never was intended to be.

The New Yorker never would have dreamed of offending its politically sheltered subscribers by giving an important skeptic like Fred Singer the chance to explain his position to them.

Though derided by global warming promoters as a hired tool of Big Oil, Singer is an expert on global climate change with a Ph.D. in physics from Princeton. He's president of the Science & Environmental Policy Project research group ( www.sepp.org ) and his dozen books include "Hot Talk, Cold Science: Global Warming's Unfinished Debate."

Singer wasn't interviewed by Kolbert. But if he had been, the man they call the "Godfather of Global Warming Denial" would have wanted The New Yorker's 2 million readers to know the single most important thing he knows about global warming:

"The question of the human contribution to climate change, the amount of it, is a matter of great scientific debate," Singer told me last week. "But no matter how it comes out, the question of global warming itself has not much scientific content and probably is of very little importance to humanity generally."

****

And in 2005 I caught the New Yorker, and Kolbert, in a mistake that was so bad it forced them to run a correction, something they almost never did.

New Yorker doesn't let facts get in the way

April 29, 2005

This global warming problem is much scarier than we thought.

Not only is the Arctic ice cap dangerously thinning, says The New Yorker in Part 1 of "The Climate of Man," its epically biased trilogy on "the realities of global warming."

But the mile-high glaciers that cover most of Greenland are melting so fast that one of them, the mighty river of ice called Jakobshavn Isbrae, has nearly doubled its speed since 1993.

According to writer Elizabeth Kolbert, who schlepped to Alaska, the Arctic and Greenland to personally observe the thawing permafrost andmelting sea ice, by 2003 the velocity of this speedy glacier "had increased to 7.8 miles per hour" from its 1993 flow-rate of "three anda half miles per hour."

And you always thought glacial meant slow.

At that Boston Marathon-competitive speed -- nearly 8 miles per hour, 192 miles a day, 6,000 miles a month -- the Jakobshavn Isbrae glacier will be knocking on the door of Rio De Janeiro by Memorial Day.

What Kolbert obviously meant to write in the April 25 issue -- and what The New Yorker's famed fact-checkers wish they had caught -- was that the glacier's speed had jumped to 7.8 miles per year .

If you prefer more precise scientific numbers, that's .00089 miles per hour, or a still-impressive 4.7 feet per hour.

Being off by a factor of 8,760 should in no way detract from the magazine's five National Magazine Awards.

Nor should it by itself discredit the politically loaded premise Kolbert set out to prove: that global warming is not a liberal hoax; that all serious scientists who are not Bush administration stooges believe it's a problem worth exchanging our SUVs for bicycles for; and that modern man is the culprit.

Though embarrassing, the speed of the glaciers is a minor mistake in an otherwise perfectly spelled 12,881-word article that deeply detailed permafrost but had no room for an honest paragraph of skepticism about the often-uncertain science behind global warming.

"The Climate of Man II," this week's offering, while mercifully shorter, is just as politically unbalanced and more of a stretch: It seeks to show that the discovery that rapid climate change apparently wiped out "large and sophisticated cultures" such as the Mayans and the Old Kingdom of Egypt presents us with "an uncomfortable precedent."

Who knows how the New Yorker's exciting serial will end next week?

Will Earth melt?

And how does Kolbert's liberal tilt compare with Mother Jones ' current cover-expose of Exxon-Mobil's generous funding of global warming skeptics?

Stay tuned -- and don't get run down by a glacier.