Q&A: Al Davis was a tough, smart winner, baby

In Oakland or LA, in the AFL or NFL, he drove his Raiders teams to pursue excellence and dominate their opponents

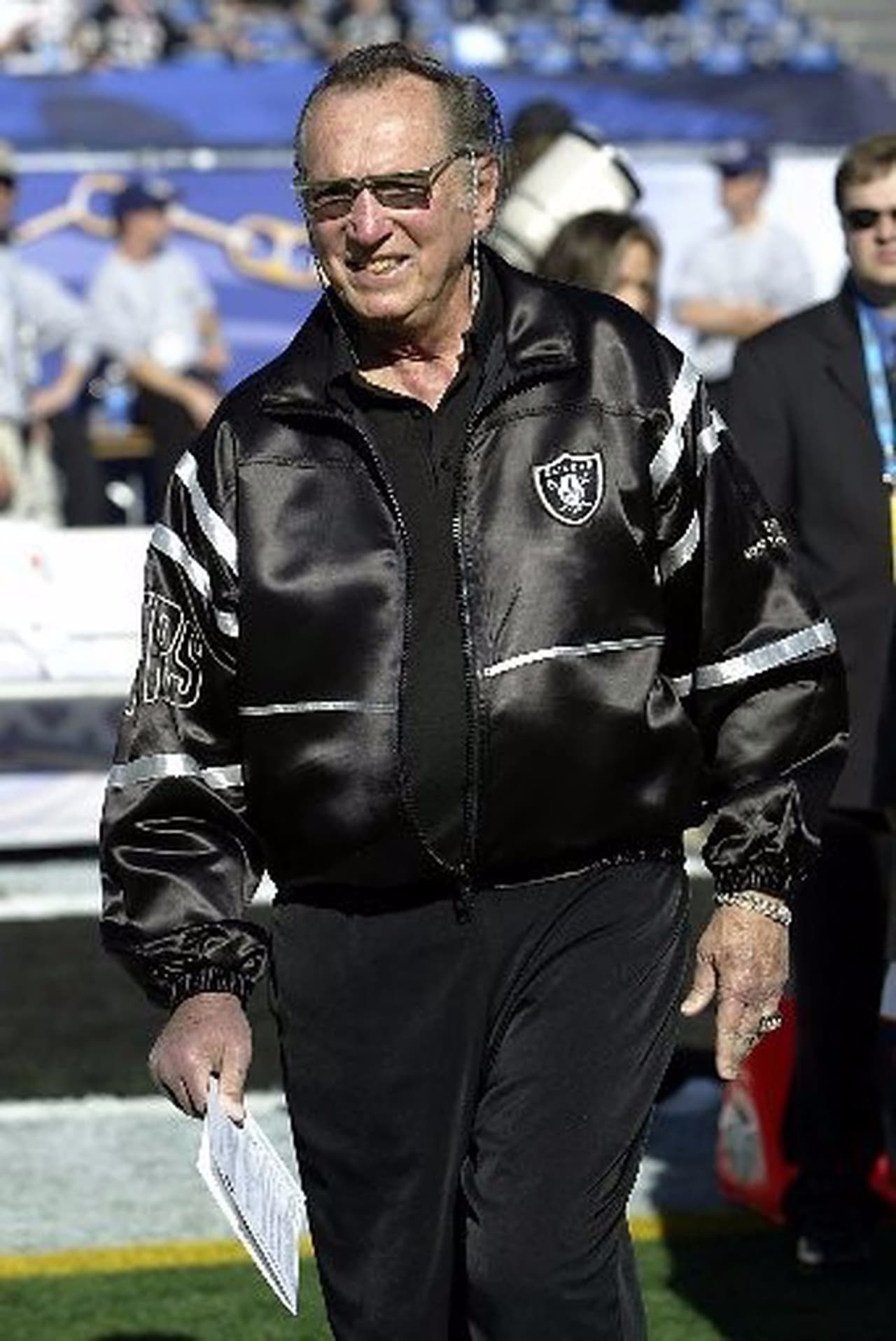

During the 1980s in Los Angeles I did dozens of freelance pieces and long interviews of famous or important people for airline magazines like AirCal. One of the scariest interviews — at first — was my visit to the underground offices of NFL tough guy Al Davis, the owner of the Oakland/Los Angeles Raiders. Davis had two oversized guys with him in his LA office who looked like they were going to beat me up if I asked the wrong question or told him I was a Pittsburgh Steeler fan, but they behaved. Davis turned out to be a really smart, perfectly nice and very forthcoming guy — yet another example of how a notorious public figure did not live up to his evil media persona in person. To mark the start of another NFL season, here is a Q&A with the one-and-only Al Davis, who died in 2011.

September, 1984

No football fan in America needs to be told who Los Angeles Raiders owner Al Davis is.

Since 1963, when he was named head coach and general manager of the then-hapless Oakland franchise of the American Football League, Davis and his silver-and-black Raiders have made winning a habit.

His teams have racked up 206 wins and 11 ties against 82 losses — a winning percentage of .715, which no pro sports team of the last two decades can match.

The Raiders, who won their third Super Bowl last January, consistently field tough, innovative, explosive teams that reflect the owner's own tenacity and tire less drive to win.

The Brooklyn-raised Davis' well-known total commitment to excellence put Oakland in the center of the football world in the '70s and early 80s, and appears to be doing the same for Los Angeles.

At 55, he is the managing general partner of an organization that eschews formal titles and fosters informality. Football is his life, and he takes an active role in all phases of the Raiders operation, from giving tips at the team's facilities in a former junior high school near the airport to working on draft picks.

Davis attended Wittenberg College and Syracuse University, where he received a degree in English and played football, basketball and baseball. He worked assistant coaching jobs at Adelphi College, The Citadel and the University of Southern California, and scouted for the Colts, before joining the staff of the newly formed Los Angeles Chargers in 1960.

In 1966 he became commissioner of the AFL and was given the job of forcing a merger with the NFL, which he accomplished in short order. Davis and his wife Carol have a son, Mark, 28.

The Raiders' controversial move from Oakland to Los Angeles just before the 1982 season is still reverberating through the courts.

The City of Los Angeles, in an effort to keep the NFL from preventing the transfer of the franchise, filed an antitrust suit against the league, which the Raiders later joined.

The City of Oakland is attempting to use the power of eminent do main to force the team back to the Bay Area. At the time of this interview in Davis' office, both court cases, which were decided in the Raiders' favor, were under appeal and still unsettled.

The Raiders stayed in LA until 1994, then moved back to Oakland until 2019, when they relocated to Las Vegas. When Davis died in 2011 at age 82, still on the job, his teams had suffered seven straight losing seasons.

Al Davis

Q: There's a certain media image of Al Davis as a tough guy, a hard-nosed, win-at-any-cost guy. Yet, others, like former Raiders coach John Madden, speak kindly of you. Have the media distorted your real character?

DAVIS: I don't really know what the media says generally about me. We like to win and I like to win, and I do have this belief and commitment to excellence. Achievement is important to me.... achievement for the entire organization.

If some say I'm hard-nosed, yeah, I am on a football field. Some say I'm a tough guy: yeah, I am. I don't think I'm tough to employees or players.

Q: Are the Raiders qualitatively nastier than other pro football teams?

DAVIS: It's conceivable. We've been accused of it. We've been accused of it by one of the toughest teams in football, the Pittsburgh Steelers.

We’re a tough football team. We attack. We're We play pressure. Pressure offense, pressure defense. The deep pass. Attack the pocket. Attack the quarterback. We believe in it. We live it. We sell it. But that's our philosophy... of toughness.

Some teams believe in intelligence. The Dallas Cowboys talk solely about intelligent players. We don't think we're the ones in this culture to judge intelligence. We think that should be done in the educational institutions.

We're looking for outstanding football players, good kids. We're looking for some who've been misunderstood, and maybe some who aren't good kids, who we can bring into our environment and change them around a little bit. Make them respond to us and the cleanliness of our environment.

We've always had great leadership. Yes, we have tough players. We've had some of the toughest players who've ever played professional sports. We're proud of them. They belong to us. I know some have bordered on the verge of illegality, but I think when you check it out they were just tough football players.

Q: Besides the obvious physical qualifications speed, strength, etc. — when you draft players, do you look at attitude, too?

DAVIS: No. We're not big on attitude. We think we can control attitude. We think when you come with the Raiders you'll I want to win. We think the environment controls most people's attitudes and forces them to act in a certain way.

In a changing society, you can either adjust your system of activities to the environment or you can migrate to some place where the environment meets your system. I've always said I'm going to stay where I am and dominate that environment, as long as I don't hurt anyone, and not adjust.

But I think most people do adjust. We've had some who are nonconformists, but we accept them. We let them play. We let them be themselves... You can't dominate Ted Hendricks. There's no way. Players like flashy Marcus Allen are primed to perpetuate the ever-growing Raider glory.

Q: When you say dominate, you don't mean forcing people to act in certain ways, do you?

DAVIS: I believe the environment forces people to act if you have a healthy environment that's part paramilitary, within the rules, and if you treat people the way they want to be treated, not the way you'd want to be treated.

I'm interested in the power that's inherent with success. The idea of winning, the idea of dominating our particular environment. I'm not minimizing the fact that the word "power" is important in the operation and in getting things done. It's the nature of our society. I don't really care what the rules are. We'll play within anybody's rules. We just want to be the best.

Q: You say you've got to dominate to get things done. Do you take that same approach to things outside football?

DAVIS: Not very much, other than life or death. I do feel you have to dominate that. The only thing that bothers me in life is death. I watched my wife comatose for 15 days. For 15 days every top doctor in America said she'd be a vegetable even if she did get up.

I just don't want to believe those things. I just believe — maybe it's a belief in God or some other force — but there's a belief that you can dominate certain things. I don't want to dominate the secretaries, or dominate the office, or dominate the financial world or anything like that. My life is pretty simple. What I want to dominate, if possible, are what I feel need to be dominated... medicine, sickness. We could do more in those areas — to help people.

Q: It doesn't necessarily mean just more money?

DAVIS: No, no. Not necessarily money? Will. Stimulus. A guy doesn't have to be a great player to be a great coach. A great coach is someone who can inspire in others the will to be great, the will to do great

Q: What impact have you had on the NFL?

DAVIS: I couldn't answer that. I really couldn't I just hope that some day this team would be recognized, if it isn't al ready, as the greatest team of all time in any sport. This organization is close right now About the only competition in the last decade was the Steelers in the 70s. I just hope we can maintain excellence, and hope we've made a tremendous contribution technically and strategy-wise.

Q: What are some of the things you've come up with? You invented the bump-and-run, didn't you?

DAVIS: Yeah, we did. When I saw (basketball coach) John Wooden use the zone pressure at UCLA, I realized that that's the direction the Raiders were going to go... as part of their philosophy. It was based on putting pressure on the offense, of not letting them come off the line of scrimmage free and clean.

Unfortunately, the minute you bring a concept into professional sports we're all copied. I watched the Steelers and Hank Stram at Kansas City copy it, and use it pretty efficiently against us.

There are so many things. A lot of people play percentage football. We don't. A lot of people say, "Take what the other team gives you." We don't. We take what we want until you show us by actual doing -- not by location or design — but by doing, that you can stop us.

Q: You don't like titles... but what's your official title?

DAVIS: The Raiders are a limited partnership. The one who has the control of the operation is the general partner. We have one general partner — me. I own about 27 percent, more than anyone else.

Q: Are you as active on a day-to-day basis as some owners, like George Steinbrenner of the Yankees?

DAVIS: I really don't know how active they are. Yeah, I'm interested. I'm active. But Tom Flores runs the team.

Q: There's no general manager, though, is there?

DAVIS: No. Actually, any one of these guys could be a general manager. It's an informal method of operation -- Ron Wolf runs the talent department, Tom Flores runs the football. I'm a novice here. I'm like an assistant in everything.

Q: But... if you're going to trade for somebody?

DAVIS: Yeah, I'll be involved.

Q: Do you always get your way?

DAVIS: No. They are a part of my life, these guys. We've all been together a long time. We don't always get along, all of us, but I think there's a respect among all of us. Most of the people have been here ten to 15 years.

Q: If you ran the NFL, would you do anything differently?

DAVIS: I'll be honest. I don't want to run the NFL. I want to run the Raiders. That's the intriguing thing... the competition, the competitive aspect of being the best — the will to win.

I don't want to run the NFL. The only thing I would have hoped was that the guy running the NFL (Pete Rozelle) would have given us the same consideration he gave many other teams in the NFL.

When I became commissioner of the American Football League in 1966, I was a head coach and a recent AFL Coach of the Year. My dream — and all the dreams I dreamed as a kid — was to be a coach, and I didn't want to give up coaching. But I know it meant the end of my coaching career to become commissioner.

I did it because the NFL was trying to destroy the AFL. I felt it was a fight, a competitive fight to destroy us — not to compete with us, but to destroy us. And I just didn't want to be destroyed.

Q: Could the NFL exist if everyone were like you — as individualistic etc.? Can a league exist with a bunch of mavericks like you in it?

DAVIS: Sure. I think it could exist. I don't know that I'm any different than most of the other owners. I really don't. It's just that my life is professional football. Most of them, their lives are independent businesses and things like that.

Q: Are there any problems in the NFL that threaten its future?

DAVIS: Obviously, the emergence on the scene — and I admire them greatly — of the United States Football League as a competitive factor that we have to face, and face intelligently. I think it's healthy. I think its good for America. I admire people who have a dream.

I think that we (the NFL) have a competitive threat from the outside and economic competition from the inside — we're 29 vicious competitors, economically. I think if we let the disparity of wealth between rich and poor teams grow, we're going to have a problem. I think if the NFL lets us compete intelligently, within a framework, we'll be alright.

Look at Baltimore. Why shouldn't the city of Indianapolis have a professional football team? In Baltimore, the Colts weren't drawing any fans. They moved to Indianapolis and within one month they sold over $30 million worth of season tickets... they have to return $22 million worth.

Someone should be there with professional football. Why can't that stadium compete for business just like shipping ports compete, just like cities compete for industry?

Q: How many teams can there be in the NFL? Fifty?

DAVIS: I don't think so. Right now I think there can only be 28. It's a question of making the economics work in relation to TV, home gate receipts, concessions, etc.

Cities ought to be able to compete. Certainly, there's a limit. But we have the same competition for players. One player just got a $40-million deal.

Q: Have players' salaries gotten out of hand? Or do you think they should get what they can?

DAVIS: I think the players are the game, and they should be rewarded. I really do. It reaches a point where you cant reward them much more than you're doing but that's when you have to say to a player. Up to then, you have to be honest and try to reward them. They deserve to be paid. Everyone has to be rewarded when you win.

Q: What were some of your reasons for leaving Oakland? What were your problems there?

DAVIS: The Raiders needed a bigger stadium, they needed luxury boxes, they needed some parking and concession money like other teams in the league. We had the highest payroll in professional football, and we had to compete for the players.

I foresaw that in the '80s, no longer would it be just hard work and intelligence, but another factor was coming into professional sports that would determine who wins -- economics.

I had to be able to compete. I saw (Oakland Athletics owner) Charlie Finley, who had three of the greatest teams in the history of sport, destroyed because he couldn't compete financially.

He had to sell his players, and he lost some in the free-agent market. I saw his dynasty destroyed. I didn't want it to happen to me.

Q: How have you been treated by the fans in Los Angeles?

DAVIS: Super, despite all the clouds of uncertainty, all the doubt. Because we had to move from Oakland to L.A. in July 1982, it made it very difficult to get set up and get our organization going. We had what we call "The Ticket Snafu." But the fans came out in a strike year — about 55,000 a game, I think.

Q: You don't expect the media to beat the drum for the Raiders...?

DAVIS: No. I hope that they do realize that our entire organization in the past two years has been in a state of transition. Our people don't know where they're going to live. It's only a problematical chance, but there's a chance we'll be forced back to Oakland, and it's been tough on our entire organization.

I don't expect the newspapers to do anything they don't want to. If they want to beat the drum for us, be proud of us and sell us, I love it. If they don't, that's their prerogative. That's America. They're free to do what they want, just like we are.

Q: Are you more public-relations conscious than you were in Oakland?

DAVIS: No. We are what we are. Quite frankly, maybe we don't do enough PR. Maybe I don't, personally. I turn down too many things. But I just feel that the players are the game, the coaches are the game. That's where the focal point should be -- on our great coaches and great players.

I've said it a hundred times—the Raiders have got the best record in professional sports in the last 21 years. Better than anyone in hockey, basketball, baseball. We've had the greatest players, greatest coaches. We've played in the greatest games...

Q: Are there people who've had an important impact on your life?

DAVIS: I loved my father and my mother, who's alive today. They were good to us. He was a well-to-do guy, but worked long hours. He was a manufacturer who owned factories and land, a hard worker.

Two guys in sports who made an impression on me were George Weiss, who ran the Yankees, and Branch Rickey, who ran the Dodgers. They opened my eyes to the fact that you could run an organization and do a great job and supply the talent and have a great philosophy, and yet not necessarily be on the field.

Q: Were there any particular coaches who taught you, or do you consider yourself self-taught?

DAVIS: Oh, no. I think the wise man in life learns by the experience of others. So I watched and learned from others. For some reason or other I had the perception to understand all this at a pretty early age.

Q: What's the biggest disappointment in your life?

DAVIS: The death of my father was probably the biggest.

Q: He was a Taft Republican. Did that rub off on you?

DAVIS: Actually, he was a Taft Republican, but there was one thing he disagreed with Taft on. Taft was more of an isolationist. My father was not. But I'm not politically oriented. I know most of the guys, but …

Q: You’re not a big campaign contributor?

DAVIS: No. Well, whatever I'd do would be private. I'm very interested in foreign affairs. I've always considered myself a strong peace-through-defense guy, but I didn't believe in Vietnam. I never could understand that.

Q: Do you have a code that you live by? Or a set of principles that you would never violate?

DAVIS: No. I just don't want to hurt others. I'm not in the mainstream where I could live by a code. I don't hang around too many people. I take care of myself, my body. I'm a square. I don't drink or smoke. I like sports, foreign affairs, people, good restaurants.

Q: Do you have any unfulfilled dreams?

DAVIS: No. I don't. I don't say we've accomplished everything, but we're doing OK.

Q: Are you a religious man?

DAVIS: I strongly believe in God and go about three times a year pay respects to my father, to say grace. I do a few other things. A religious man? No. But I do believe there's more to it than just us.

Q: Are you a happy man?

DAVIS: Yeah. I think I am. I really am. I think!

Q: In spite of all the legal problems? You're on top now...

DAVIS: Well, I've always been on top ever since I was a kid. I think problems are normal in life. What most people would call "problems," I would call something we've got to solve, something we've got to get a solution to and take care of in the normal course of business. Not respond to it as a special case. I treat problems as normal.

I think problems are the people who are poor, the people who are sick — those are problems. What we're doing is kid stuff.

Q: How will the Raiders do this season?

DAVIS: As said when came here in 1982, with all our great years and with all the glory, I still thought the greatness of the Raiders was in the future. In 1982 we were good, in '83 we were excellent, and in '84 we have a chance to be real good again.

But it doesn't matter what I think, or what we say, or what we talk. In our society, there's only one thing that counts — who wins at the end. And that's what we gotta do if we're going to be successful.

The Raiders' goals are a lot different than a lot of peoples'. A lot of people are content making the playoffs, a lot are content having winning seasons. Our season is not a success unless we're the dominant team at the end.

Ex-newspaperman Bill Steigerwald is the author of 30 Days a Black Man, which retells the true story of Pittsburgh Post-Gazette star reporter Ray Sprigle's undercover mission through the Jim Crow South in 1948. Sprigle's original series is in Undercover in the Land of Jim Crow. Steigerwald also wrote Dogging Steinbeck, which exposed the truth about the fictions and fibs in Travels With Charley and celebrated Flyover America and its people.