Looking for ghosts in North Dakota

This from 'Dogging Steinbeck' describes what I found -- and didn't find -- in Alice, N.D., on Oct. 12, 2010. Exactly 50 years earlier John Steinbeck said he met an itinerant actor there. He didn't.

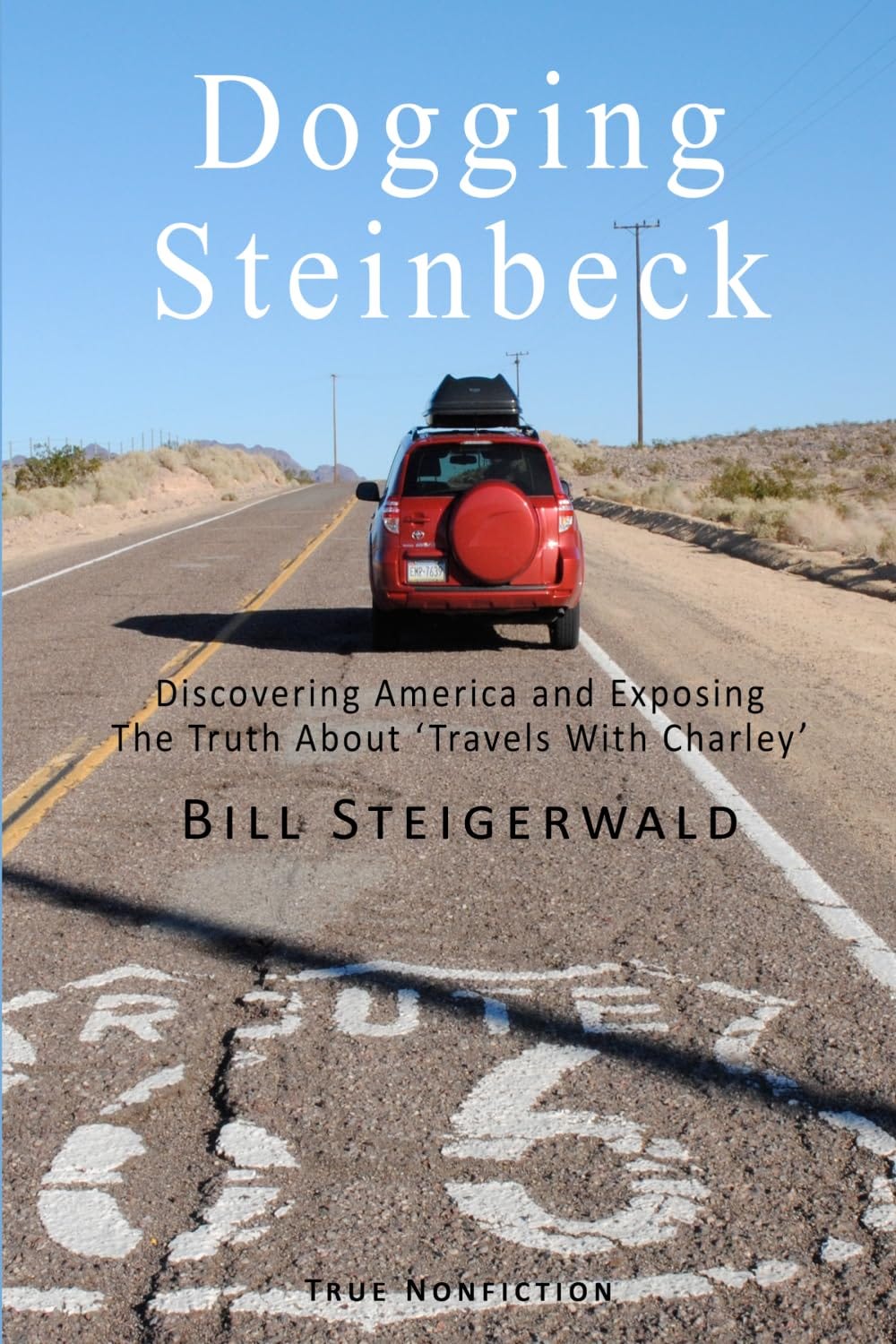

Introduction to ‘Dogging Steinbeck’

I discovered two important and surprising truths when I retraced the route John Steinbeck took around the country in 1960 and turned into his Travels with Charley in Search of America.

I found out the great author’s iconic “nonfiction” road book was a deceptive, dishonest and highly fictionalized account of his actual 10,000-mile road trip.

And I found out that despite the Great Recession and national headlines dripping with gloom and doom, America was still a big, beautiful, empty, healthy, rich, safe, clean, prosperous and friendly country.

Dogging Steinbeck is the story of my adventures on and off the road with John Steinbeck’s ghost in 2010. This excerpt is about my stop in the middle of North Dakota’s empty oceanic wheat fields, where Steinbeck wrote in “Travels With Charley” he bumped into a traveling Shakespearean actor.

12 – Makin’ Time in North Dakota

Steinbeck Timeline

Wednesday, Oct. 12, 1960 – Beach, North Dakota

Sticking to U.S. 10, Steinbeck moves from Frazee, Minnesota, through Fargo and Bismarck to Beach, North Dakota, a small agricultural town near the Montana border. He drives about 425 miles, almost straight west. In Beach he checks into a small motel, probably the Westgate, and has a bath.

Town Without People

Steinbeck had romantic ideas about the city of Fargo and he was looking forward to seeing it for the first time. But when he drove through its downtown on Wednesday morning Oct. 12, 1960, he apparently got swept along in the traffic and didn’t stop. I had a similar experience in Fargo when crossing over the Red River of the North into North Dakota from Detroit Lakes. The “West 10” signs I was following vanished and I ended up on North Broadway Drive. In the lunch-hour rush I inched bumper-to-bumper past the Fargo Theater, the city’s signature downtown landmark, and the stone-faced Fargo National Bank.

Steinbeck’s description of Fargo in Travels with Charley shows how much information a great writer can pack into half a sentence: “… it was a golden autumn day, the town as traffic-troubled, as neon-plastered, as cluttered and milling with activity as any other up-and-coming town of forty-six thousand souls.” Except that there were more than twice as many Fargonians alive in 2010, that sounded like the town we both briefly met. Fargo and its “broken-metal-and-glass outer-ring,” as Steinbeck called its trashy outskirts, extended farther west into the void of eastern North Dakota than when he complained about it. I didn’t see any auto graveyards or landfills. But soon the malls, pawnshops, car dealers, tank farms and fairgrounds evaporated. U.S. 10 West and its signs vanished, too, buried forever under Interstate 94.

The land west of Fargo on I-94 was flat and wide, un-peopled and plowed to the max – like it’d been since about 1900, I’d bet. Turning off the interstate at County Road 38, which went nowhere in two directions, I went south toward the town of Alice, where Steinbeck says in Charley he camped out overnight. North Dakota is the fourth least densely populated state and most of it is farmland, facts that would surprise no one driving across it. The combines I saw from Route 38 looked like ants, and there were more combines on the horizons than houses. Traffic simply did not exist.

From outer space, Alice is a little splash of civilization spilled on a gigantic grid of farmland and perfectly straight roads. Everything around Alice is disturbingly parallel and perpendicular, except one thing – the drunken Maple River. Starting northwest of Alice and flowing south, it wriggles and wanders for miles, doubling back on itself, forming little pools, disappearing into wetlands and almost encircling Alice before trickling northeast to join larger rivers and lakes that ultimately empty into Hudson Bay.

I was looking forward to Alice. I had Google Mapped it before my trip and it wasn’t really a town or even a village. From its satellite photo, it looked more like an unfinished, poorly zoned suburban development – a random scattering of a few dozen homes, buildings, a church or two, with a lot of empty space tied together with what looked like gravel roads.

When I arrived in Alice at 3:30 in the afternoon, no one was there to greet me. That was because hardly a soul is left in Alice. When Steinbeck wrote about it, it had only about 160 inhabitants, but it still had all the proper parts of a town. By 2010 Alice was down to 50 humans. The post office was closed. So was the town grain silo, the town school and the town Catholic Church, St. Henry’s. It still had a mayor. And the town cemetery was still alive and well, though it was going to run out of dead people long before it ran out of space.

Steinbeck says in the first draft of Travels with Charley that he “found a pleasant place to stop on the Maple River just north of Alice.” While there alone, away from the road, he says an itinerant Shakespearean actor pulled in and parked his trailer not far from him. Steinbeck describes the actor in minute detail. He had a classic profile and wore a leather jacket, olive-drab trousers and a cowboy hat with “the brim curled and held to a peak by the chin strap.” Eventually the two men share coffee and whisky and discourse for five boring pages about the joys and sorrows of the acting profession. The tedious scene could have been worse. Steinbeck originally had the actor deliver 20-lines of Hamlet’s “To be or not to be” rap. Wisely, that overt hunk of page filler was cut from the first draft.

The actor says when he performed Shakespeare on the road, he respectfully borrowed the “words, tones and inflections” of John Gielgud. Then he pulls out a treasured letter he kept folded in his wallet. It was from Sir John himself. Steinbeck quotes the brief note in full. His lucky encounter with the actor, long on dialogue, is rich in specifics and detail. But it never happened.

A Farmer Gets the Joke

Two miles west of Alice, near the vacant intersection of 45th and 137th streets, I stood next to an impenetrable dry cornfield on an elevated farm road. It was the highest ground for miles. It was sunny and warm, but the chilly wind whipped up whitecaps on the small lake nearby and slapped little high-frequency waves against its grassy shore. I was looking for signs of the Maple River – what in Pennsylvania we’d more accurately call Maple Creek.

It was there that the absurdity of what Steinbeck tried to pull on his readers really hit me. I already knew from a letter he sent to his wife that he lied in Charley about camping overnight in Alice. I also knew he didn’t bump into his quotable thespian soul mate. Not anywhere near Alice, anyway, and not in the theatrical, stilted way he described. But standing in the middle of that middle of nowhere, trying to imagine anyone meeting anyone else there at all – I really did laugh out loud. You had to be there with all that corn and farmland to appreciate the joke.

I was still laughing when I found a farmer, or he found me. He was running a big blue Ford tractor, pulling a disk plough that magically turned a wide swath of his soft green field to black. Looking as pathetic as possible, I hailed him. He climbed down from his cab to see what was wrong with my car or my head. We were both wearing blue jeans, T-shirts and baseball caps, but he was wearing work boots and, presumably, socks.

After I explained what I was doing, he trusted me with the basic facts of his life as long as I promised not to tell the whole World Wide Web his name. He was 50, the son of a farmer and a farmer himself for 23 years. He had what he called a “smallish” farm – 1,400 acres, a little over 2 square miles. He grew half wheat and half soybeans, not just corn like most of his neighbors, because he said wheat doesn't take as many people or trucks to produce.

I didn’t pry into his finances. But an Internet business directory listed his company as having $95,000 in annual revenue and a staff of 1, which I assumed was him. The only help the farmer had was his wife, two daughters and a good credit line. His wife – he pointed to a dust cloud half a mile away – was running the family combine. His older daughter ran it when she wasn’t away at college.

I told the farmer what Steinbeck said he did near Alice. Then I asked if he knew a spot nearby where Steinbeck might have camped overnight by the Maple River and met a traveling Shakespearean actor with a John Gielgud letter in his wallet. He looked around, got the joke and laughed.

In Travels with Charley Steinbeck states without equivocation that he camped overnight near Alice. He didn’t. In the real world, the nonfiction world, he passed by Alice on Wednesday, Oct. 12, 1960. It was Day 3 of his 2,100-mile, seven-day sprint from Chicago to Seattle and he spent it crossing the entire state of North Dakota.

In the morning he may have paused for several hours along the Maple River somewhere near Alice. It’s even possible he met an itinerant Shakespearean actor – or a man from Mars.

But in a day that started in Frazee, Minnesota, Steinbeck logged about 425 miles before stopping for the night in Beach, North Dakota, an agricultural town in the Badlands near the Montana border. By sundown Wednesday he was already 321 miles past Alice, about to take a hot bath in a motel. We know all this is true because it’s what he told his wife in a letter he wrote that night from Beach.

Alice wasn’t the only overnight campout in North Dakota that Steinbeck invented. The next night he didn’t sleep under the stars in the spooky Badlands, either. In Charley Steinbeck beautifully describes how the slanting evening sunlight warmed the strange and harsh landscape of the Badlands, how he built a fire, how the starry night was filled with sounds of hunting screech owls and barking coyotes, and how the “night was so cold that I put on my insulated underwear for pajamas.”

It was total fiction. On Thursday night, Oct. 13 – Day 4 of his Chicago-Seattle sprint – he was actually already 400 miles west of Beach and the Badlands. He was in Livingston, Montana, watching the third Nixon-Kennedy TV debate at a trailer court. Because he was moving so quickly from Chicago to Seattle, Steinbeck was forced to make up two overnight camping adventures in North Dakota and stick them in between his actual stays in Frazee and Beach.

Steinbeck’s two flights of “creative nonfiction” under the stars in North Dakota are important, but not just because they are such bald-faced fabrications. Along with his non-meeting with the Yankee farmer in New Hampshire, they are the scenes in the book that created the myth that he was traveling slowly, camping out and roughing it alone in the American outback.

After snapping a corncob in half and telling me it was fit only for ethanol, the friendly farmer went back to his disking. For half an hour I drove to several places where farm roads intersected with the tiny Maple River as it squirmed through the tall grass.

I didn’t know it then, but there were a dozen possible places west, south or east of Alice where the river meets a road. Bumping into a sophisticated thespian anywhere near Alice – or anywhere else – would have been a fantastic bit of good luck for any traveling writer. It wasn’t impossible. It’s just that it doesn’t happen like that in the real world.

I left the cornfields near Alice and aimed for Bismarck, 165 miles west on I-94. Somewhere in the hilly terrain I crossed the Continental Divide. The elevation was only 1,490 feet because, though North Dakota is rich in oil and gas and energy jobs, it’s poor in mountain ranges. In Bismarck, where the supply of motels was not keeping pace with the demand from the energy boom, I couldn’t find a room under $125, but I was more than happy to check in at the nearest Walmart.

###