Flyover America -- According to New Yorkers

For 50 years John Steinbeck and his fellow travelers set sail into the hinterlands from New York City with the same cargo of elitist clichés about what’s wrong with America and its deplorable people.

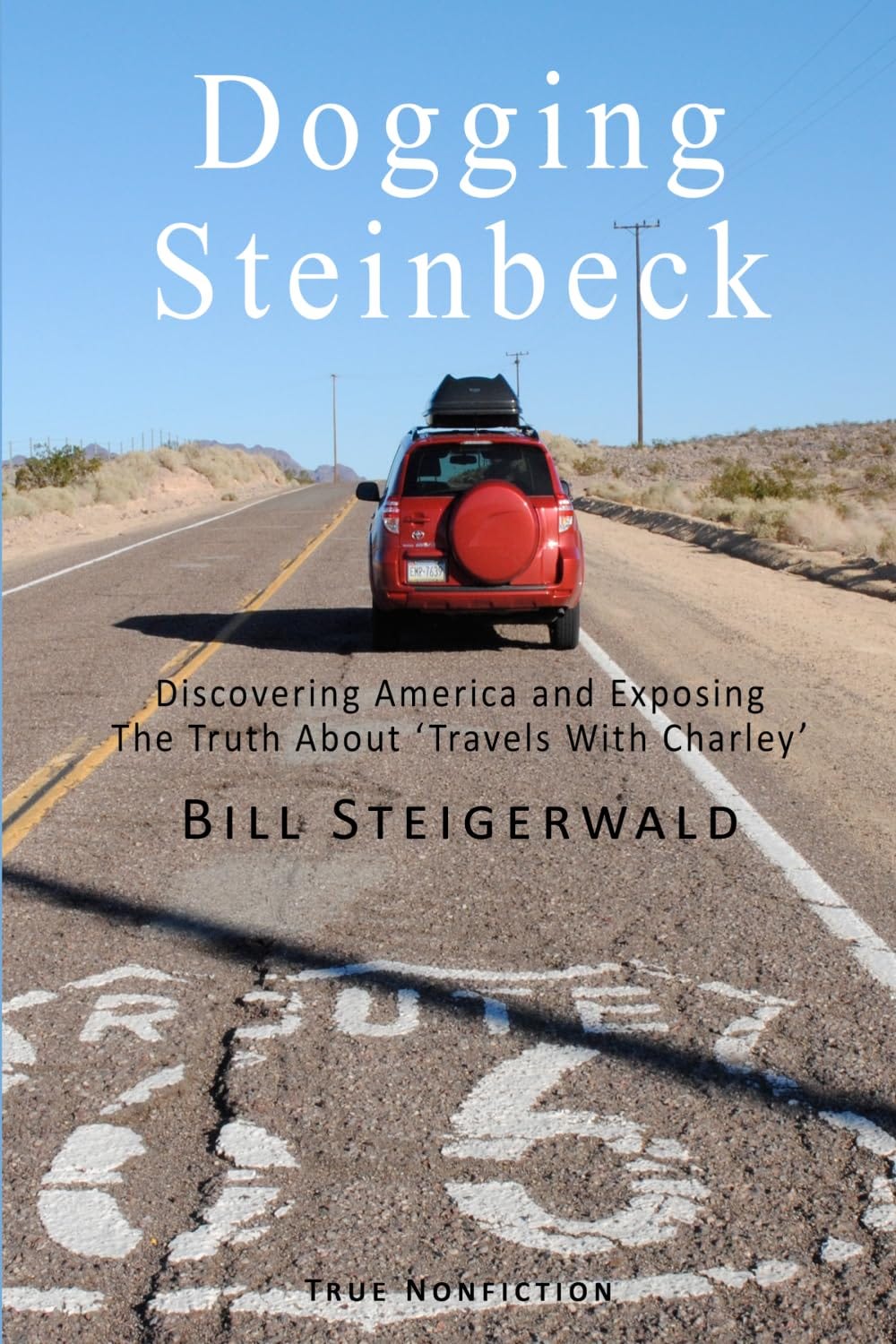

Introduction to ‘Dogging Steinbeck’

I discovered two important and surprising truths when I retraced the route John Steinbeck took around the country in 1960 and turned into his Travels with Charley in Search of America.

I found out the great author’s iconic “nonfiction” road book was a deceptive, dishonest and highly fictionalized account of his actual 10,000-mile road trip.

And I found out that despite the Great Recession and national headlines dripping with gloom and doom, America was still a big, beautiful, empty, healthy, rich, safe, clean, prosperous and friendly country.

Dogging Steinbeck is the story of my adventures on and off the road with John Steinbeck’s ghost in 2010. This excerpt is my defense of Flyover America 2010 and its people — the people who soon were going to put Donald Trump into the White House — twice.

Dogging Steinbeck

America according to New Yorkers

In 2008, as the American economy plummeted into the Great Recession and Barack Obama was riding the Hope and Change Express to the White House, Bill Barich decided to drive across America. Barich’s book about his road trip, Long Way Home: On the Trail of Steinbeck’s America, was inspired by a re-reading – as an adult – of Travels with Charley.

Barich, a California native in his late 60s, has written for the New Yorker, authored eight books and lived in Ireland for about a decade. He wanted to see if Steinbeck’s gloomy prophecy about the decline of America and his concern about the moral flabbiness of its people was finally coming true. He didn’t retrace the Steinbeck Highway. For about six weeks he crossed the waist of America from New York City to San Francisco, roughly on U.S. Route 50, which meant he, like Steinbeck and I, saw a whiter, more rural, more Republican small-town America.

Barich thought Steinbeck’s private opinion of an America in decay was distorted because Steinbeck was depressed, in poor health and spent too much time alone on his Charley trip, which is a laugh I’ll address a few dozen paragraphs from now. But Barich took most of the author’s other critiques of 1960 America more seriously. He told The New York Times he thought Steinbeck’s “perceptions were right on the money about the death of localism, the growing homogeneity of America, the trashing of the environment. He was prescient about all that.”

It’s no surprise Barich, an expatriated liberal writer exploring the conservative heart of Red State America, agreed with Steinbeck’s sociopolitical and cultural complaints. For 50 years Barich, Steinbeck and their fellow travelers have set sail into the hinterlands from New York City with the same cargo of elitist clichés about what’s wrong with America.

Not to stereotype their views too unfairly, but folks like Barich instinctively believe a caricature of Flyover America. They believe the country west of the Hudson and east of the Hollywood sign is overpopulated, over-sprawled, over-malled, devoid of culture, polluted, ruined by national chains and strangled with congested freeways.

Barich made no effort to hide his cultural and political biases. He decried “the pernicious malls and ugly subdivisions” he said were a permanent, unfixable part of America. He also agreed with Steinbeck on some negative points, including that Americans were “frequently lax, soft, and querulous, and they sometimes capitulated to a childish sense of entitlement.”

As for Barich’s politics, they were as predictable as a New York Times editorial. He made the obligatory complaint about America’s “divisive (i.e., conservative) talk-show pundits.” He repeated the insulting but common fable that whenever hinterland conservatives criticize Barack Obama or Big Government in Washington they are parroting one of Rush Limbaugh’s “latest proclamations that consciously stoke the fear and paranoia of Americans.”

He also mocked Sarah Palin and the white Middle Americans who came to worship her at a Republican rally in Wilmington, Ohio. “The faces tilted up to her were as vacant as those of stoned kids at a rock concert, absent of any emotion except surrender,” Barich wrote. He was not exaggerating about the adoring crowd. But he was being unfair and unbalanced.

I happened to attend a Palin rally in 2008 – her first one – as a journalist. The day after her selection as McCain’s VP, on a blisteringly hot August Saturday, she appeared with him at a minor league baseball field 20 minutes from my house south of Pittsburgh. It was like a rock concert – for 10,000 desperately hopeful middle-aged Republicans.

Hanging on a cyclone fence taking photos, I got close enough to Palin to see the dark ring of sweat on her collar as she shook hands and snuggled babies. The crowd was totally nuts for her, especially the women. No one cared about John McCain or what Palin said in her stump speech, which was word-for-word what she had said on TV the day before. They had clearly come to cheer and hope – and yes, adore.

Barich didn’t attend a Barack Obama campaign event on his trip. But every little dig he made about the Palin rally and the Republican crowd’s embarrassing enthusiasm for their unprepared heroine also could have been said about the hopers & dreamers packing a typical Obama rally. Not that Barich would have ever considered making fun of Obama’s idolaters.

Though politically predictable, Barich wasn’t a total Steinbeck yes man. He pointed out that the author missed some positives about America – for example, the vast wildernesses that had been saved and “the potential rewards of new technologies.” But Barich concurred with many of Steinbeck’s complaints about Americans not being able to handle their hard-earned glut of affluence and comfort.

Barich characterized his fellow countrymen as “friendly, well-intentioned, good humored, kind, and generous, but also loud, aggressive, clumsy, gullible, and poorly educated.” Naturally, he said he preferred Europe’s older quieter, gentler, more sophisticated – i.e., more socialist – societies, where “pernicious malls” and “divisive” talk shows aren’t so free to disturb the order of things.

That’s fine what Barich thought. He paid his commentator’s dues. He drove the hard miles, so he got to throw his conventional liberal wisdom and biases around in his book. Like Steinbeck’s book and this one, his account of what he saw and thought was purely subjective. It was filtered by his previous experiences, worldview, values and politics and was subject to the randomness and serendipity of the road. All obvious stuff, but it’s rarely noted and always worth repeating in our ruthlessly subjective universe. It’s something Steinbeck pointed out as well in Charley.

Barich was more hopeful about the country’s long-term future than Steinbeck was in 1960. That was a refreshing twist on the usual New York-centric gloom and doom. But you get the sense that Barich’s optimism had more to do with the victory of Barack Obama than what he found on his solo tour of America’s midsection, which he described as “alternately grand and awful, sublime and stomach-turning, both a riddle and a paradox.”

America Unchained

Like all stereotypes, the Hollywood/Manhattan stereotype of America and its Flyover People is based on reality. But its main ingredient – besides its premise of moral, cultural and intellectual superiority – is exaggeration. Take over-population. Sure, big cities are densely populated. That’s kind of what great, dynamic, productive urban centers are supposed to be. That’s how they generate economic wealth and new ideas.

But anyone who drives 50 miles in any direction in an empty state like Maine or North Dakota – or even in north-central Ohio or Upstate New York – can see America’s problem is not overpopulation. More often it’s under-population. Cities like Butte and Buffalo and Gary have been virtually abandoned. Huge hunks of America on both sides of the Mississippi have never been settled. From Calais to Pelahatchie, I passed down the main streets of comatose small towns whose mayors would have been thrilled to have to deal with the problems of population growth and sprawl. In a dozen states, I cruised two- and four-lane highways so desolate I could have picnicked on them.

If anyone thinks that rural Minnesota, northwestern Montana, the Oregon Coast, the Texas Panhandle or New Orleans’s Upper Ninth Ward have been homogenized, taken over by chains or destroyed by suburban sprawl and too much commercial development, it’s because they haven’t been there. It’s a 50-year-old myth that America has been conquered and homogenized by national chains. It wasn’t close to being true in 1960, when Steinbeck was worrying about corner groceries being wiped out by the mega-grocer A&P, the largest restaurant chain in the country was Howard Johnson’s and Holiday Inn of America was three years old.

Today restaurant and motel chains cling to interstate exits, where the heavy traffic is, and they clone themselves in the upscale suburbs. But try to find a Bob Evans, a Holiday Inn Express or a burger joint with a familiar name in a small town or in the sticks. You better like McDonald’s or Subway, because in most of the Zip Codes I was in those were your only choices – if you were lucky.

The America I traveled was unchained from sea to sea. I had no problem eating breakfast, sleeping or shopping for road snacks at mom & pop establishments in every state. The motels along the Oregon and Maine coasts are virtually all independents that have been there for decades. Here’s a post-trip stat I saw from the American Hotel & Lodging Association that didn’t surprise me a bit: Of the country’s 52,215 motels and hotels with 15 units or more, 22,200 are independent – i.e., not affiliated with a chain. You can go the length of old Route 66 and never sleep or eat in a chain unless you choose to. Same for U.S. Route 101 in Oregon and Northern California.

Steinbeck, like many others have since, lamented the loss of regional customs. (I don’t think he meant the local “customs” of the Jim Crow South or the marital mores of the Jerry Lee Lewis clan.) Pockets of regional culture are not as concentrated and isolated as they once were, which is a blessing for the median national IQ and the English language, but they’re not extinct and there are many new pockets.

I didn’t go looking for Native Americans, Amish, Iraqis in Detroit, Peruvians in northern New Jersey or the French-Canadians who have colonized the top edge of Maine. But I had no trouble spotting local flavor in Wisconsin’s dairy lands, in fishing towns along Oregon’s coast, in the redwood-marijuana belt of Northern California, in San Francisco’s Chinatown and the cattle country of Texas.

As for the demise of local dialects, it too is exaggerated by those who find such culturally backward things quaint and worth preserving. In Maine, Texas and Louisiana I met white Anglo-Saxon Americans whose accents were so heavy I wasn’t always sure they were speaking English. I’ll never forget Duke Shepard of Deer Isle.

In the last 10 years, I’ve had the same experience in the Mississippi Delta, southern West Virginia and the hollers of eastern Kentucky, where I met a proud hillbilly who’d be debunked as a crude 1930s stereotype if he appeared in a movie. (He kept his ex-wife in a converted chicken coop and had two sons in prison, one for murder.) Pittsburgh’s steel-making jobs may have disappeared, but its distinct working-class accent hasn’t. Just listen to a C-SPAN call-in show for a random hour and you’ll hear hard American accents that six decades of TV have done nothing to soften.

Again, not to generalize, but the New York-Hollywood elites believe in a cultural caricature. They think the average Flyover Person lives in a double-wide or a Plasticville suburb, eats only at McDonald’s, votes only Republican, shops only at Walmart and the Dollar Store, hates anyone not whiter than they are, speaks in tongues on Sunday and worships pickup trucks, guns and NASCAR the rest of the week.

Those stereotypes and caricatures are alive and well in Flyover Country. But though I held radical beliefs about government, immigration and drugs that could have gotten me lynched in many places, I never felt I was in a country I didn’t like or didn’t belong in. Maybe I just didn’t go to enough sports bars, churches and political rallies.

Yes, Americans were materialistic as hell. They could afford to be, thanks to the incredible democratization of wealth and luxury that’s occurred in the last 50 years. Hundreds of millions of Americans were enjoying the kind of lifestyle that only 1-Per-Centers like Steinbeck could afford in 1960. Steinbeck – and ex-pats like Barich living like lords in Ireland – have a lot of nerve complaining about the greedy materialism of America’s commoners when they themselves already have every material goodie they need or want.

The hundreds of ordinary Americans I bumped into were real, not made up and not composites. They were unique, hard-working people who were living longer, better, richer lives than Steinbeck could have dreamed. Unlike Steinbeck, who met one unlikable, sour, grammatically challenged person after another (or said he did), I met a procession of happy, friendly saints. I’m not a touchy-feely guy. And I know that as an old white guy by myself I was a threat to no one. But I was treated so well, I fell in love with every other American I met. For five minutes, anyway.

I have to agree wholeheartedly with what Bill says here, and I am a broken-down old white Biden liberal. However, I have a home in rural Northern Michigan, and there are wonderful little independent restaurants scattered in all sorts of out-of-the way places, some of which have better food than you would pay four times as much for in NYC.