Casting call for Denzel Washington (or Samuel L. Jackson or Clifton Duncan)

Now's a perfect time for Denzel to produce & co-star in a movie about how John Wesley Dobbs helped make civil rights history in 1948 by guiding an undercover white reporter through the Jim Crow South.

Many thanks to my Pittsburgh pal and excellent syndicated newspaper columnist Tom Purcell.

He used the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday to make a public pitch to Denzel Washington to produce and star in a movie about John Wesley Dobbs, a under-heralded early civil rights leader and orator from Atlanta whom every American should know about.

Dobbs, an important figure in the black community from the 1930s through the 1950s, knew his neighbor, young Martin Luther King Jr., very well and was an important influence on him.

But the brave deed Dobbs did in 1948 — at age 66 — is what is most worthy of Hollywood’s — or Netflix’s — attention.

A star Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reporter, Ray Sprigle, 61, had decided to disguise himself as a light-skinned black man from the North and go undercover into the Jim Crow South. He wanted to see for himself what life was like for 10 million blacks living separate and unequal lives under America’s apartheid.

When asked by the head of the NAACP to guide Sprigle safely around the Deep South’s segregated and unequal black society, Dobbs — despite the danger to himself — agreed enthusiastically.

Dobbs drove the reporter from Savannah to the Delta, introducing him to sharecroppers, black professionals and black leaders. He hosted him at his home in Atlanta and made sure Sprigle didn’t get in trouble with the KKK or the racists who ran everything and strictly enforced Jim Crow’s web of oppressive, humiliating laws.

Dobbs’ collaboration with Sprigle created a national sensation in the white media — the first one of its kind about the immorality and un-Americanism of legal race segregation.

In his bitter, powerful, 21-part nationally syndicated newspaper series, Sprigle shocked the mostly oblivious white people of the North with details of what he had seen, felt and experienced.

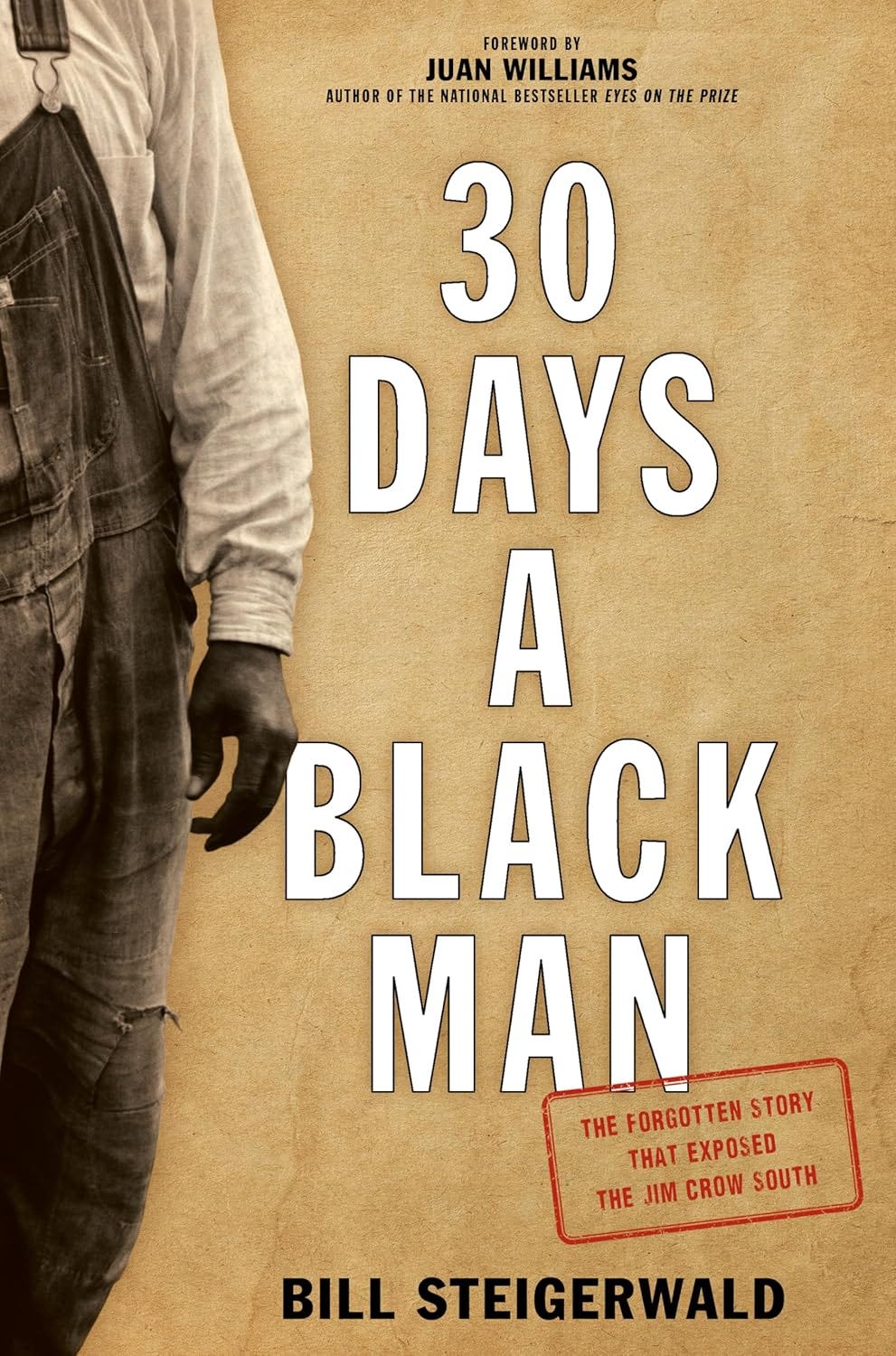

His pioneering journalism is now largely forgotten. But the details of Sprigle’s journey and the impact his series had on the whole country is told in detail in my 2017 history book '30 Days a Black Man.' His original Post-Gazette series is reprinted in full here.

Finally, getting back to Denzel. If you know him, please tell him to have his people give my people (me) a call. Film rights are still available.

John Wesley Dobbs

Excerpts from ‘30 Days a Black Man’

From my book, here are some paragraphs describing John Wesley Dobbs:

— Dobbs and Sprigle are cruising through the Delta in Dobbs' 47 Mercury 8....

The only genuine black man in the speeding Mercury was the leadfooted sixty-six-year-old driver, John Wesley Dobbs. Arguably the most influential black political and civic figure in Atlanta, he was a celebrated public speaker who had two cars and owned a handsome house in the wealthiest black neighborhood in America.

Confident and driven, a flask of whiskey in his inside coat pocket, Dobbs could quote long poems and passages from Shakespeare from memory and often preached his favorite civil rights gospel that the only way for blacks to achieve full freedom and equality was through the three Bs—“Bucks, Ballots and Books.”

It was May 27, 1948. Ray Sprigle had come down into the Deep South to see—and feel—for himself how ten million black American lived under the system of legal segregation known as Jim Crow. For nearly three weeks he had been eating, sleeping, and living as a black man.

Dobbs was his guide to the black world. Because he was the longtime grand master of Georgia’s Prince Hall Masons fraternal group, he was known and trusted by middle-class blacks across the South. In Atlanta and in the small towns of rural Georgia, Alabama, and Tennessee, Dobbs was introducing the undercover journalist to black doctors and undertakers, to sharecroppers, and to the families of lynching victims. When he told them Sprigle was gathering information for the NAACP, they believed it.

Dobbs was also Sprigle’s driver and protector. He knew how to comfortably and safely travel the South’s dirt and clay back roads, where for black motorists the bathrooms were usually in the bushes and an “uppity” black man in a nice car could quickly find himself in serious trouble with white folks or the county sheriff.

Dobbs and Sprigle meet for the first time:

How the two collaborators greeted each other will never be known. What is known is that on Friday, May 7, 1948, Ray Sprigle and John Wesley Dobbs met each other for the first time somewhere inside the monstrous granite caverns of Washington, DC’s Union Station. As they sized each other up, thousands of commuters and travelers surged through the station’s concourses or sat on the long mahogany benches under the high vaulted ceiling of its waiting room.

Sprigle had traveled 240 miles by train that day from Pittsburgh. When he boarded his passenger coach, he was a free, famous, and fairly affluent white American. When he got off in Washington, he was James Crawford, a light-skinned black American of modest means who was subject to the local ordinances and indignities of Jim Crow.

Sprigle had traded his tailored suits and business shoes for an ordinary gray suit coat, a stiff cotton shirt, baggy cuffed dress pants, wide suspenders, and unshined ankle-high work shoes. An oversized checkered newsboy’s cap hid his bald, well-tanned head and drooped over the heavy black frames of his eyeglasses. In his pockets were his corncob pipe, a pouch of Granger tobacco, a small spiral notebook, several pencils, and a travel wallet with his “James Rayel Crawford” Social Security card.

Everything else he was taking into the South, including some tablets and fake paperwork to prove he was “a smalltime writer and smalltime office holder,” he carried in a worn leather doctor’s bag. His new skin color, in his own words, was “a passable coffee-with-plenty-of-cream shade.”

Sprigle’s partner Mr. Dobbs needed no disguise. He was his usual self — bigger than life. With his shiny set of luggage and three-piece suit, he looked like a cross between a movie star and the Ambassador of Ethiopia. He wore a gold Masonic stickpin and a subtle cloud of cologne. A watch dangled from his vest pocket. He looked, acted, and spoke like a man who played hardball with white politicians, taught black history to college kids, gave speeches on national radio, and had his own parking space when he went to see the Atlanta Black Crackers play at Ponce DeLeon Park.

Sprigle knew Dobbs was a historic figure.

Dobbs was destined for the history books. He was a classic American success story who had lifted himself out of deep rural poverty and overcome the South’s soul-grinding system of discrimination. In thirteen years Martin Luther King Jr. was going to speak at Dobbs’s funeral and his friend Thurgood Marshall was going to be one of his pallbearers. The street he lived on in Atlanta’s best black neighborhood was going to be renamed after him and a giant sculpture of his head was going to be placed on the sidewalk of Auburn Avenue, the Main Street of black Atlanta.

Sprigle made his living extracting the relevant or interesting facts of any person’s story, no matter how humble or boring they were. But Dobbs’s remarkable life was a feature writer’s gold mine. He was born in 1882 on a farm about thirty miles northwest of Atlanta, near the Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield.

Like so many of his generation, his parents were ex-slaves. He was also the grandson of a white slave owner named McAfee who had fathered his mother Minnie during the first years of the Civil War. After his parents split up when he was two years old, Dobbs was raised nearby on a farm in Marietta by his paternal grandparents.

Living with more than a dozen young uncles, aunts, and cousins in two log cabins, he grew up barefoot and poor a hundred yards from a railroad line. The ghostly faces looking out the windows of passenger coaches were the only white people he saw. He went to a black school three months a year, but when he was nine he joined his single-mother Minnie in Savannah and began school there full time. When a white woman learned he was to be pulled out of school because his mother could no longer afford to buy him the clothes or shoes he needed, the woman gave him a job so he could buy them himself.

For the rest of his life Dobbs never stopped working. His jobs included delivering the Savannah Evening Press and shining shoes at a barbershop. At age fifteen he moved to Atlanta and accomplished something fewer than 10 percent of all Americans—white or black, North or South—did in his era: He got a high school diploma. He was intelligent, hardworking, and driven at an early age to become a successful black man in a white man’s world. He started college at what would soon become Morehouse College, but had to quit after only a few months to tend to his sick mother.

Knowing a federal job was one of the few places a black man in the South could escape Jim Crow’s reach and earn enough to achieve a middle-class lifestyle, he took a civil service test. In 1903, at age twentyone, he became a US Post Office clerk who sorted mail on the Nashville & Atlanta railroad. It was a highly respected position that not only paid him the princely starting salary of eight hundred dollars a year, but also allowed him to carry a Colt revolver. The only black man working on the train, he stayed at his job for thirty-two years, eventually becoming the boss of a crew of white men.

In 1906 he married Irene Ophelia Thompson, bought a house on Houston Street in Atlanta’s best black neighborhood for $2,767, and began filling it with a piano, hundreds of books, and six children, all girls.

Though he never received his college degree, Dobbs never stopped educating himself. He studied literature, history, and philosophy all his life. On his layovers in Nashville, the young mail clerk spent his nights reading. In a notebook he called his “Armory of Ideas,” he wrote down quotes he liked from the writings of Aesop, Frederick Douglass, Jefferson Davis, Booker T. Washington, and W. E. B. Du Bois. He also made up quotes of his own including “I cannot conquer age; all other fights I can win,” which became his mantra for the rest of his life.

He memorized long stanzas of English poetry and passages from Shakespeare, but most of all he was a history nut. He studied black history and learned it so well he taught it in college classes and once presented a lecture on CBS national radio. He read books about Napoleon, the Romans, the Greeks, and Abraham Lincoln, his greatest hero and the reason he was a Republican.

He visited Lincoln’s birthplace in Kentucky so many times that the guides knew him by name. Eternally thankful for what Lincoln and the Union armies did to end slavery, he would faithfully stop at Civil War battlefields in the North and South to pay his respects to the Union dead.

In 1911, at age twenty-nine, Dobbs changed his life forever by joining the Prince Hall Masons, the black version of the Masons fraternal group that appealed to socially conscious middle-class black men like him. The Prince Hall Masons were started in the late 1700s in New England because white Masons wouldn’t admit blacks. They established lodges and temples in cities across the country, though most were concentrated in the South where the majority of blacks lived. To be admitted, you needed recommendations from Prince Hall members. Plus you needed what Dobbs already possessed—a good reputation in the community, a strong belief in God and Christian values, and an initiation fee of $7.50.

Dobbs quickly worked his way up through the ranks of the Atlanta grand lodge. In the mid-1920s, while still a mail clerk, he became head of the lodge’s financial department, a position that paid him more than his government job. In 1932, three years before he retired from the Post Office, Dobbs was elected the grand master of the Prince Hall Masons of Georgia.

He made full use of his near-dictatorial powers and his managerial skills to increase the membership and clout of the state’s masons. The duties of the grand master—visiting local lodges and settling any disputes over money or membership issues—meant he traveled extensively on Prince Hall business.

“The Grand,” as he was reverentially called, was greeted like a celebrity in black communities throughout the state. A thunderous and dramatic orator, he delivered well-constructed speeches at Prince Hall affairs in Cleveland and Detroit. Whether he was addressing hundreds of Masons, a church congregation, or just “preaching” to a few citizens he’d cornered on the sidewalk, he always pushed the same subversive political message—the key to the advancement of the his race was the ballot box.

He was always the consummate “race man”—a black man who devoted his life to bettering and defending his race by confronting—peacefully—the institutions, people, and ideas that held them back.

After Dobbs retired with a pension from the Post Office in 1935, he concentrated on building his race into a political force the city’s white power structure had to reckon with. On February 12, 1936, by no accident Lincoln’s birthday, he called a public meeting at Atlanta’s largest black church and announced the formation of the Atlantic Civic and Political League.

In a rousing two-hour speech at Big Bethel A.M.E. Church, he proclaimed that the city’s ninety thousand blacks were never going to get decent public schools for their kids, black police officers for their neighborhoods, equal pay for their teachers, or decent city parks for their old folks unless at least ten thousand of them registered to vote. Until they could deliver a large bloc of black votes to white politicians on Election Day, they were never going to have the political leverage they needed to improve their lives.

On the day Dobbs started his organization and named himself its president, there were six hundred registered black voters in Atlanta. Three years later there were nearly three thousand. Though he was a Lincoln man to his soul, Dobbs had an eight-year fling with FDR and the New Deal Democrats. In the fall of 1936 he was invited to join Roosevelt’s re-election campaign by the Democratic National Committee and went north to speak to black voter groups in Rhode Island, New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland.

In a 1939 interview with an oral historian for the Library of Congress, as part of the Federal Writers Project, Dobbs said he accepted the “assignment and duty because of my sincere belief in the progressive principles advocated by theNew Deal administration, especially as they related and are interpreted toward the uplifting and betterment of living conditions for poor people regardless of race, color, or creed.”

Through the war years Dobbs never stopped banging the drum for black voter registration in Masonic halls, churches, college campuses, and at the Butler Street YMCA, where Atlanta’s black leaders often met to plan and argue. By 1944 he had soured on President Roosevelt, deciding he had not been so progressive after all when it came to helping poor blacks or challenging the power of segregationist Democrats in the Senate. He returned to the Republican fold, becoming a Georgia delegate committed to New York governor Thomas Dewey at the GOP national convention. Dobbs favored the moderate-to-liberal Dewey largely because of his strong civil rights record.

In 1946 he cofounded the Atlanta Negro Voters League, which also urged blacks to register and vote. During this time Dobbs took his moral and political message on the road. In the summer of 1947, for example, he was paid to speak at least eight times at black colleges and Prince Hall Mason events from Ohio to Atlantic City to Savannah….

A month before he met Sprigle in Washington, DC, Dobbs had proudly watched an event on Auburn Avenue that he had worked for years to achieve. In payment for the promise he made—and kept—to deliver a bloc of ten thousand votes to incumbent white mayor Bill Hartsfield in a Democratic primary election, eight black policemen made their debut on the streets of Atlanta. They could only patrol black neighborhoods, the only whites they could arrest were drunks and vagrants, and they were stationed in the basement of the black YMCA. But integratin the police force was a major symbolic victory for Dobbs and his allies. It proved the foundation of segregation could be cracked if blacks learned when and where to hit it with their votes. When Dobbs watched black cops walk down Auburn Avenue in their uniforms for the first time, at his side was his ten-year-old grandson, Maynard Holbrook Jackson Jr., the future mayor of Atlanta.

Sprigle was a worldly and intelligent man, not easily impressed. He had met and interviewed hundreds of political and corporate big shots in his career. His friends included US senators, the governor of Pennsylvania, and future Pennsylvania Supreme Court justice Michael Musmanno, the author and presiding judge for one of the war crimes trials held in military court at Nuremberg in 1947.

If Sprigle had any doubts that the man sitting next to him on the train did not belong in their league, they would have disappeared if he read the transcript of Dobbs’s long interview in 1939 with the Library of Congress.

Dobbs was fifty-seven at the time. He told his interviewer about his poor beginnings, his early love of learning, his struggle to educate himself, and how much his many jobs taught him about human nature and getting ahead in life.

He said he was “a great believer in self-help. All I wanted was an opportunity to work.” He expressed his love of America, the Constitution, and “people’s human rights.” He said his immediate goal was “to awaken the Atlanta Negroes to their civic and political consciousness” and get them to exercise their vote for their own benefit. But his ultimate ambition was for every black American to be made a full and equal citizen with all of the same rights and privileges guaranteed by the US Constitution.

“Over the doorway of the nation’s Supreme Court building in Washington, DC,” he said, “are engraved four words, ‘Equal Justice Under Law.’ This beautiful American ideal is what the Negroes want to see operative and effective from the Atlantic to the Pacific and from the Great Lakes to the Gulf—nothing more or less.”

Later in that long Library of Congress interview, during which he impressed the interviewer by reciting forty-nine lines of Edwin Markham’s poem “The Man with the Hoe,” Dobbs said he was embarrassed to be talking so much about himself and his accomplishments.

But he said, “Whatever I have accomplished, if there is anything, I have done it from sheer determination and because I looked up and saw the stars. I have struggled to be useful to mankind. . . . I made up my mind at an early age to do something and I guess I can sum it all up by saying I can compare myself with the two ships:

“ ‘One ship sails east, the other sails west by the same wind that blows. It’s the set of the sail and not the gale that determines the course as she goes.’ I set my ‘sails’ to rise above poverty and ignorance and whatever the ‘gale’ I still kept my mind on what I wanted to accomplish in life, and each day I have tried to do those things that would reflect credit on me, my family, and my race. I have devoted my life and my talents to helping pave the right road for my people.”

Everyone in the country should read 30 Days a Black Man