Jitneys were Pittsburgh's answer to racist, monopoly taxicabs

Illegal car service in black neighborhoods provided simple, cheap, reliable and safe transportation for decades. This article is from 1994, but jitneys were not put out of business by Uber.

Jitneys were — and still are — an important mode of transportation in the black neighborhoods of Pittsburgh. August Wilson, aka “The Black Shakespeare,” wrote his play “Jitney” about the characters working at a Hill District “jitney station,” where drivers awaited calls for car service from local people.

The jitney system — which is free-market, completely illegal but virtually unpoliced — relied on entrepreneurial drivers, word of mouth and cash. It was essentially Uber before there was Uber and it still operates today in Pittsburgh, where Uber and Lyft have done a community service by destroying the Yellow Cab monopoly that lasted 70 years and ill-served blacks (and suburbanites).

City's invisible transit system is cheap, thriving and illegal

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Oct. 24, 1994

Jitneys private cars used as taxis by their owners to make money are completely illegal, but that hasn't stopped them from operating openly on the streets of Pittsburgh tor more than 60 years.

Collectively, they form an invisible, unofficial urban transit system, primarily for Pittsburgh's black and poor neighborhoods, that carries more passengers than all of Pittsburgh's legal cab companies combined.

The jitney system wasn't designed by experts and its fares and routes are not regulated, planned, subsidized or taxed by any government agency. Yet this underground taxi service works very well for several thousand people every day. It provides simple, cheap, reliable and safe transportation for its clientele.

Everyone knows jitneys exist — from the state Public Utility Commission, whose laws they violate, to the Port Authority Transit and Yellow Cab, whose customers they take.

But despite their illegality, no law enforcement agency does much of anything to discourage jitneys. That, according to Otto Davis, is not only probably the wise thing to do, it's a public blessing.

Davis is an economics professor at Carnegie Mellon University who has studied Pittsburgh's jitneys extensively. He believes they should be made legal and that their development should be encouraged.

Every major city he knows has illegal jitneys, says Davis. It's hard to know for sure, he says, but anywhere from 500 to 1,000 jitney drivers operate in the Pittsburgh area.

Typically, they are older, retired black men who work four or five hours a day and earn less than $10,000 a year. Jitneys were once perfectly legal and flourished here and in every other American city, says Davis.

The cheap, highly popular "five-cent cars" — the term jitney is slang for "nickel" — cruised trolley lines, stealing many passengers and millions of dollars in revenues from city-owned or city-franchised trolley companies.

By 1918, however, most cities had passed ordinances to outlaw jitneys, primarily because of political pressure from trolley lobbies. Taxicabs, then considered an off-peak-hour luxury service, were inadvertently left out of the restrictive legislation aimed at jitneys.

Jitneys, though outside the law, have since become an old and trusted institution in Pittsburgh's black neighborhoods and elsewhere. They come in three basic varieties. Every weekday, "line-haul" jitneys can be observed driving in a steady, inconspicuous parade down Fifth Avenue into Downtown, their drivers double-beeping at each bus stop as a signal for their passengers to climb in.

Line-haul jitneys come along more frequently than the Port Authority buses they compete with. On a Monday afternoon at the corner of Fifth and Smithfield across from Kaufmann's clock, 10 passengers were picked up in 30 minutes.

They were whisked away in seven big, older American four-door cars with no fanfare and no disruption of traffic. Fares on the "line" are what buses charge —$1.25. Jitneys can also be found parked day or night at the Greyhound station and at the Am-trak station, where they compete directly against taxis and sometimes run afoul of authorities for taking up parking spaces.

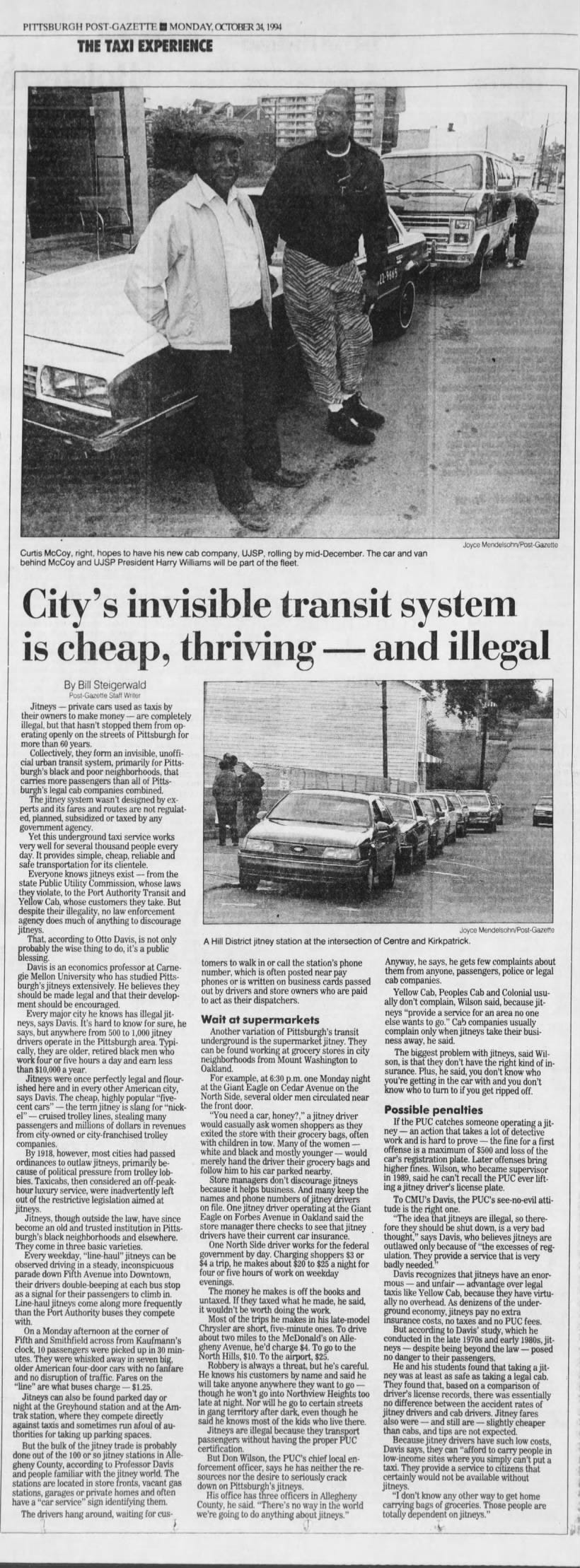

But the bulk of the jitney trade is probably done out of the 100 or so jitney stations in Allegheny County, according to Professor Davis and people familiar with the jitney world.

The stations are located in store fronts, vacant gas stations, garages or private homes and often have a "car service" sign identifying them. The drivers hang around, waiting for customers to walk in or call the station's phone number, which is often posted near pay phones or is written on business cards passed out by drivers and store owners who are paid to act as their dispatchers.

Another variation of Pittsburgh's transit underground is the supermarket jitney. They can be found working at grocery stores in city neighborhoods from Mount Washington to Oakland.

For example, at 6:30 p.m. one Monday night at the Giant Eagle on Cedar Avenue on the North Side, several older men circulated near the front door.

"You need a car, honey?" a jitney driver would casually ask women shoppers as they exited the store with their grocery bags, often with children in tow. Many of the women — white and black and mostly younger — would merely hand the driver their grocery bags and follow him to his car parked nearby.

Store managers don't discourage jitneys because it helps business. And many keep the names and phone numbers of jitney drivers on file. One jitney driver operating at the Giant Eagle on Forbes Avenue in Oakland said the store manager there checks to see that jitney drivers have their current car insurance.

One North Side driver works for the federal government by day. Charging shoppers $3 or $4 a trip, he makes about $20 to $25 a night for four or five hours of work on weekday evenings.

The money he makes is off the books and untaxed. If they taxed what he made, he said, it wouldn't be worth doing the work. Most of the trips he makes in his late-model Chrysler are short, five-minute ones. To drive about two miles to the McDonald's on Allegheny Avenue, he'd charge $4. To go to the North Hills, $10. To the airport, $25.

Robbery is always a threat, but he's careful. He knows his customers by name and said he will take anyone anywhere they want to go though he won't go into Northview Heights too late at night.

Nor will he go to certain streets in gang territory after dark, even though he said he knows most of the kids who live there. Jitneys are illegal because they transport passengers without having the proper PUC certification.

But Don Wilson, the PUC's chief local enforcement officer, says he has neither the resources nor the desire to seriously crack down on Pittsburgh's jitneys.

His office has three officers in Allegheny County, he said. "There's no way in the world we're going to do anything about jitneys." Anyway, he says, he gets few complaints about them from anyone, passengers, police or legal cab companies.

Yellow Cab, Peoples Cab and Colonial usually don't complain, Wilson said, because jitneys "provide a service for an area no one else wants to go." Cab companies usually complain only when jitneys take their business away, he said. The biggest problem with jitneys, said Wilson, is that they don't have the right kind of insurance.

Plus, he said, you don't know who you're getting in the car with and you don't know who to turn to if you get ripped off.

If the PUC catches someone operating a jitney — an action that takes a lot of detective work and is hard to prove — the fine for a first offense is a maximum of $500 and loss of the car's registration plate.

Later offenses bring higher fines. Wilson, who became supervisor in 1989, said he can't recall the PUC ever lifting a jitney driver's license plate.

To CMU's Davis, the PUC's see-no-evil attitude is the right one.

"The idea that jitneys are illegal, so therefore they should be shut down, is a very bad thought," says Davis, who believes jitneys are outlawed only because of "the excesses of regulation. They provide a service that is very badly needed."

Davis recognizes that jitneys have an enormous — and unfair — advantage over legal taxis like Yellow Cab, because they have virtually no overhead. As denizens of the underground economy, jitneys pay no extra insurance costs, no taxes and no PUC fees.

But according to Davis' study, which he conducted in the late 1970s and early 1980s, jitneys — despite being beyond the law — posed no danger to their passengers. He and his students found that taking a jitney was at least as safe as taking a legal cab.

They found that, based on a comparison of driver's license records, there was essentially no difference between the accident rates of jitney drivers and cab drivers. Jitney fares also were — and still are — slightly cheaper than cabs, and tips are not expected.

Because jitney drivers have such low costs, Davis says, they can "afford to carry people in low-income sites where you simply can't put a taxi. They provide a service to citizens that certainly would not be available without jitneys.

"I don't know any other way to get home carrying bags of groceries.